Difference between revisions of "Integration Formulas and the Net Change Theorem"

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Therefore, since <math>\frac{1}{x}</math> is the derivative of <math>\ln(x)</math> we can conclude that | Therefore, since <math>\frac{1}{x}</math> is the derivative of <math>\ln(x)</math> we can conclude that | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| + | <math>\int\frac{dx}{x}=\ln|x|+C</math> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

Note that the polynomial integration rule does not apply when the exponent is <math>-1</math> . This technique of integration must be used instead. Since the argument of the natural logarithm function must be positive (on the real line), the absolute value signs are added around its argument to ensure that the argument is positive. | Note that the polynomial integration rule does not apply when the exponent is <math>-1</math> . This technique of integration must be used instead. Since the argument of the natural logarithm function must be positive (on the real line), the absolute value signs are added around its argument to ensure that the argument is positive. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

:<math>\frac{d}{dx}e^x=e^x</math> | :<math>\frac{d}{dx}e^x=e^x</math> | ||

we see that <math>e^x</math> is its own antiderivative. This allows us to find the integral of an exponential function: | we see that <math>e^x</math> is its own antiderivative. This allows us to find the integral of an exponential function: | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | <math>\int e^xdx=e^x+C</math> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

===Integral of Sine and Cosine=== | ===Integral of Sine and Cosine=== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 51: | ||

So <math>\sin(x)</math> is an antiderivative of <math>\cos(x)</math> and <math>-\cos(x)</math> is an antiderivative of <math>\sin(x)</math> . Hence we get the following rules for integrating <math>\sin(x)</math> and <math>\cos(x)</math> | So <math>\sin(x)</math> is an antiderivative of <math>\cos(x)</math> and <math>-\cos(x)</math> is an antiderivative of <math>\sin(x)</math> . Hence we get the following rules for integrating <math>\sin(x)</math> and <math>\cos(x)</math> | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| − | + | <math>\int\cos(x)dx=\sin(x)+C</math></br><math>\int\sin(x)dx=-\cos(x)+C</math> | |

| − | + | </blockquote> | |

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

| Line 64: | Line 69: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | ==Recognizing Derivatives and Reversing Derivative Rules== | ||

| + | If we recognize a function <math>g(x)</math> as being the derivative of a function <math>f(x)</math> , then we can easily express the antiderivative of <math>g(x)</math> : | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int g(x)dx=f(x)+C</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, since | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\frac{d}{dx}\sin(x)=\cos(x)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | we can conclude that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int\cos(x)dx=\sin(x)+C</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similarly, since we know <math>e^x</math> is its own derivative, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int e^xdx=e^x+C</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The power rule for derivatives can be reversed to give us a way to handle integrals of powers of <math>x</math> . Since | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\frac{d}{dx}x^n=nx^{n-1}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | we can conclude that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int nx^{n-1}dx=x^n+C</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | or, a little more usefully, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int x^ndx=\frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}+C</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Finding Area or Net Change Between Curves== | ||

| + | Finding the area between two curves, usually given by two explicit functions, is often useful in calculus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In general the rule for finding the area between two curves is | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>A=A_{\rm top}-A_{\rm bottom}</math> or | ||

| + | |||

| + | If f(x) is the upper function and g(x) is the lower function | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>A=\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is true whether the functions are in the first quadrant or not. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Area between two curves== | ||

| + | Suppose we are given two functions <math>y_1=f(x)</math> and <math>y_2=g(x)</math> and we want to find the area between them on the interval <math>[a,b]</math> . Also assume that <math>f(x)\ge g(x)</math> for all <math>x</math> on the interval <math>[a,b]</math> . Begin by partitioning the interval <math>[a,b]</math> into <math>n</math> equal subintervals each having a length of <math>\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}</math> . Next choose any point in each subinterval, <math>x_i^*</math> . Now we can 'create' rectangles on each interval. At the point <math>x_i*</math> , the height of each rectangle is <math>f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)</math> and the width is <math>\Delta x</math> . Thus the area of each rectangle is <math>\bigl[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\bigr]\Delta x</math> . An ''approximation'' of the area, <math>A</math> , between the two curves is | ||

| + | :<math>A:=\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\Big]\Delta x</math> . | ||

| + | Now we take the limit as <math>n</math> approaches infinity and get | ||

| + | :<math>A=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\Big]\Delta x</math> | ||

| + | which gives the exact area. Recalling the definition of the definite integral we notice that | ||

| + | :<math>A=\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx</math> . | ||

| + | This formula of finding the area between two curves is sometimes known as applying integration with respect to the ''x''-axis since the rectangles used to approximate the area have their bases lying parallel to the ''x''-axis. It will be most useful when the two functions are of the form <math>y_1=f(x)</math> and <math>y_2=g(x)</math> . Sometimes however, one may find it simpler to integrate with respect to the ''y''-axis. This occurs when integrating with respect to the ''x''-axis would result in more than one integral to be evaluated. These functions take the form <math>x_1=f(y)</math> and <math>x_2=g(y)</math> on the interval <math>[c,d]</math> . Note that <math>[c,d]</math> are values of <math>y</math> . The derivation of this case is completely identical. Similar to before, we will assume that <math>f(y)\ge g(y)</math> for all <math>y</math> on <math>[c,d]</math> . Now, as before we can divide the interval into <math>n</math> subintervals and create rectangles to approximate the area between <math>f(y)</math> and <math>g(y)</math> . It may be useful to picture each rectangle having their 'width', <math>\Delta y</math> , parallel to the ''y''-axis and 'height', <math>f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)</math> at the point <math>y_i^*</math>, parallel to the ''x''-axis. Following from the work above we may reason that an ''approximation'' of the area, <math>A</math> , between the two curves is | ||

| + | :<math>A:=\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)\Big]\Delta y</math> . | ||

| + | As before, we take the limit as <math>n</math> approaches infinity to arrive at | ||

| + | :<math>A=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)\Big]\Delta y</math> , | ||

| + | which is nothing more than a definite integral, so | ||

| + | :<math>A=\int\limits_c^d \bigl(f(y)-g(y)\bigr)dy</math> . | ||

| + | Regardless of the form of the functions, we basically use the same formula. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Closed path integral defined.png|Closed_path_integral_defined]] | ||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

* [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Indefinite_integral Indefinite Integral], Wikibooks: Calculus | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Indefinite_integral Indefinite Integral], Wikibooks: Calculus | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Area Area], Wikibooks: Calculus | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Integration_techniques/Recognizing_Derivatives_and_the_Substitution_Rule Recognizing Derivatives and Substitution Rule], Wikibooks: Calculus | ||

* [https://youtu.be/df1Qr8pepx0 Net Change Theorem, Definite Integral & Rates of Change Word Problems, Calculus] by the Organic Chemistry Tutor | * [https://youtu.be/df1Qr8pepx0 Net Change Theorem, Definite Integral & Rates of Change Word Problems, Calculus] by the Organic Chemistry Tutor | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Licensing== | ||

| + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Indefinite_integral Indefinite Integral, Wikibooks: Calculus] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Area Area, Wikibooks: Calculus] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 13:17, 28 October 2021

Contents

Indefinite integral identities

Basic Properties of Indefinite Integrals

Constant Rule for indefinite integrals

- If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle c} is a constant then }}

Sum/Difference Rule for indefinite integrals

- }}

Indefinite integrals of Polynomials

Say we are given a function of the form, , and would like to determine the antiderivative of . Considering that

we have the following rule for indefinite integrals:

Power rule for indefinite integrals

- for all

Integral of the Inverse function

To integrate Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x)=\frac{1}{x}} , we should first remember

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\ln(x)=\frac{1}{x}}

Therefore, since Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{1}{x}} is the derivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \ln(x)} we can conclude that

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int\frac{dx}{x}=\ln|x|+C}

Note that the polynomial integration rule does not apply when the exponent is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -1} . This technique of integration must be used instead. Since the argument of the natural logarithm function must be positive (on the real line), the absolute value signs are added around its argument to ensure that the argument is positive.

Integral of the Exponential function

Since

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}e^x=e^x}

we see that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle e^x} is its own antiderivative. This allows us to find the integral of an exponential function:

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int e^xdx=e^x+C}

Integral of Sine and Cosine

Recall that

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\sin(x)=\cos(x)}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\cos(x)=-\sin(x)}

So Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sin(x)} is an antiderivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cos(x)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -\cos(x)} is an antiderivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sin(x)} . Hence we get the following rules for integrating Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sin(x)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cos(x)}

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int\cos(x)dx=\sin(x)+C}

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int\sin(x)dx=-\cos(x)+C}

Example

Suppose we want to integrate the function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x)=x^4+1+2\sin(x)} . An application of the sum rule from above allows us to use the power rule and our rule for integrating Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sin(x)} as follows,

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int f(x)dx} Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle =\int\Big(x^4+1+2\sin(x)\Big)dx} Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle =\int x^4dx+\int 1\,dx+\int 2\sin(x)dx} Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle =\frac{x^5}{5}+x-2\cos(x)+C} .

Recognizing Derivatives and Reversing Derivative Rules

If we recognize a function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle g(x)} as being the derivative of a function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x)} , then we can easily express the antiderivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle g(x)} :

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int g(x)dx=f(x)+C}

For example, since

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\sin(x)=\cos(x)}

we can conclude that

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int\cos(x)dx=\sin(x)+C}

Similarly, since we know Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle e^x} is its own derivative,

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int e^xdx=e^x+C}

The power rule for derivatives can be reversed to give us a way to handle integrals of powers of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x}

. Since

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}x^n=nx^{n-1}}

we can conclude that

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int nx^{n-1}dx=x^n+C}

or, a little more usefully,

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \int x^ndx=\frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}+C}

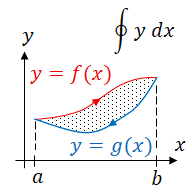

Finding Area or Net Change Between Curves

Finding the area between two curves, usually given by two explicit functions, is often useful in calculus.

In general the rule for finding the area between two curves is

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=A_{\rm top}-A_{\rm bottom}} or

If f(x) is the upper function and g(x) is the lower function

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx}

This is true whether the functions are in the first quadrant or not.

Area between two curves

Suppose we are given two functions Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y_1=f(x)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y_2=g(x)} and we want to find the area between them on the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [a,b]} . Also assume that for all on the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [a,b]} . Begin by partitioning the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [a,b]} into Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} equal subintervals each having a length of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}} . Next choose any point in each subinterval, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x_i^*} . Now we can 'create' rectangles on each interval. At the point Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x_i*} , the height of each rectangle is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)} and the width is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta x} . Thus the area of each rectangle is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \bigl[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\bigr]\Delta x} . An approximation of the area, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A} , between the two curves is

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A:=\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\Big]\Delta x} .

Now we take the limit as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} approaches infinity and get

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(x_i^*)-g(x_i^*)\Big]\Delta x}

which gives the exact area. Recalling the definition of the definite integral we notice that

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx} .

This formula of finding the area between two curves is sometimes known as applying integration with respect to the x-axis since the rectangles used to approximate the area have their bases lying parallel to the x-axis. It will be most useful when the two functions are of the form Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y_1=f(x)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y_2=g(x)} . Sometimes however, one may find it simpler to integrate with respect to the y-axis. This occurs when integrating with respect to the x-axis would result in more than one integral to be evaluated. These functions take the form Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x_1=f(y)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x_2=g(y)} on the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [c,d]} . Note that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [c,d]} are values of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y} . The derivation of this case is completely identical. Similar to before, we will assume that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(y)\ge g(y)} for all Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y} on Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [c,d]} . Now, as before we can divide the interval into Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} subintervals and create rectangles to approximate the area between Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(y)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle g(y)} . It may be useful to picture each rectangle having their 'width', Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta y} , parallel to the y-axis and 'height', Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)} at the point Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y_i^*} , parallel to the x-axis. Following from the work above we may reason that an approximation of the area, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A} , between the two curves is

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A:=\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)\Big]\Delta y} .

As before, we take the limit as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} approaches infinity to arrive at

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[f(y_i^*)-g(y_i^*)\Big]\Delta y} ,

which is nothing more than a definite integral, so

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A=\int\limits_c^d \bigl(f(y)-g(y)\bigr)dy} .

Regardless of the form of the functions, we basically use the same formula.

Resources

- Indefinite Integral, Wikibooks: Calculus

- Area, Wikibooks: Calculus

- Recognizing Derivatives and Substitution Rule, Wikibooks: Calculus

- Net Change Theorem, Definite Integral & Rates of Change Word Problems, Calculus by the Organic Chemistry Tutor

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- Indefinite Integral, Wikibooks: Calculus under a CC BY-SA license

- Area, Wikibooks: Calculus under a CC BY-SA license