Difference between revisions of "The Derivative"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

If {{math|''f''}} is differentiable at {{math|''a''}}, then {{math|''f''}} must also be continuous at {{math|''a''}}. As an example, choose a point {{math|''a''}} and let {{math|''f''}} be the step function that returns the value 1 for all {{math|''x''}} less than {{math|''a''}}, and returns a different value 10 for all {{math|''x''}} greater than or equal to {{math|''a''}}. {{math|''f''}} cannot have a derivative at {{math|''a''}}. If {{math|''h''}} is negative, then {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is on the low part of the step, so the secant line from {{math|''a''}} to {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is very steep, and as {{math|''h''}} tends to zero the slope tends to infinity. If {{math|''h''}} is positive, then {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is on the high part of the step, so the secant line from {{math|''a''}} to {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} has slope zero. Consequently, the secant lines do not approach any single slope, so the limit of the difference quotient does not exist. | If {{math|''f''}} is differentiable at {{math|''a''}}, then {{math|''f''}} must also be continuous at {{math|''a''}}. As an example, choose a point {{math|''a''}} and let {{math|''f''}} be the step function that returns the value 1 for all {{math|''x''}} less than {{math|''a''}}, and returns a different value 10 for all {{math|''x''}} greater than or equal to {{math|''a''}}. {{math|''f''}} cannot have a derivative at {{math|''a''}}. If {{math|''h''}} is negative, then {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is on the low part of the step, so the secant line from {{math|''a''}} to {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is very steep, and as {{math|''h''}} tends to zero the slope tends to infinity. If {{math|''h''}} is positive, then {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} is on the high part of the step, so the secant line from {{math|''a''}} to {{math|''a'' + ''h''}} has slope zero. Consequently, the secant lines do not approach any single slope, so the limit of the difference quotient does not exist. | ||

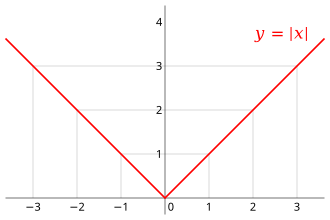

| − | [[File:Absolute value.svg|right|thumb|The absolute value function is continuous, but fails to be differentiable at | + | [[File:Absolute value.svg|right|thumb|The absolute value function is continuous, but fails to be differentiable at <math>x = 0</math> since the tangent slopes do not approach the same value from the left as they do from the right.]] |

However, even if a function is continuous at a point, it may not be differentiable there. For example, the absolute value function given by {{math|''f''(''x'')}} = |''x''| is continuous at {{math|''x''}} = 0, but it is not differentiable there. If {{math|''h''}} is positive, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to {{math|''h''}} is one, whereas if {{math|''h''}} is negative, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to {{math|''h''}} is negative one. This can be seen graphically as a "kink" or a "cusp" in the graph at {{math|''x''}} = 0. Even a function with a smooth graph is not differentiable at a point where its tangent is vertical: For instance, the function given by {{math|''f''(''x'')}} = {{math|''x''<sup>1/3</sup>}} is not differentiable at {{math|''x''}} = 0. | However, even if a function is continuous at a point, it may not be differentiable there. For example, the absolute value function given by {{math|''f''(''x'')}} = |''x''| is continuous at {{math|''x''}} = 0, but it is not differentiable there. If {{math|''h''}} is positive, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to {{math|''h''}} is one, whereas if {{math|''h''}} is negative, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to {{math|''h''}} is negative one. This can be seen graphically as a "kink" or a "cusp" in the graph at {{math|''x''}} = 0. Even a function with a smooth graph is not differentiable at a point where its tangent is vertical: For instance, the function given by {{math|''f''(''x'')}} = {{math|''x''<sup>1/3</sup>}} is not differentiable at {{math|''x''}} = 0. | ||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

Here the second term was computed using the chain rule and third using the product rule. The known derivatives of the elementary functions ''x''<sup>2</sup>, ''x''<sup>4</sup>, sin(''x''), ln(''x'') and exp(''x'') = ''e''<sup>''x''</sup>, as well as the constant 7, were also used. | Here the second term was computed using the chain rule and third using the product rule. The known derivatives of the elementary functions ''x''<sup>2</sup>, ''x''<sup>4</sup>, sin(''x''), ln(''x'') and exp(''x'') = ''e''<sup>''x''</sup>, as well as the constant 7, were also used. | ||

| − | == | + | == Licensing == |

| − | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derivative Derivative | + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: |

| + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derivative Derivative, Wikipedia] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 11:23, 6 November 2021

In mathematics, the derivative of a function of a real variable measures the sensitivity to change of the function value (output value) with respect to a change in its argument (input value). Derivatives are a fundamental tool of calculus. For example, the derivative of the position of a moving object with respect to time is the object's velocity: this measures how quickly the position of the object changes when time advances.

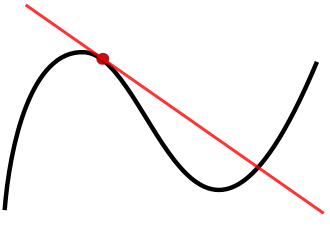

The derivative of a function of a single variable at a chosen input value, when it exists, is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function at that point. The tangent line is the best linear approximation of the function near that input value. For this reason, the derivative is often described as the "instantaneous rate of change", the ratio of the instantaneous change in the dependent variable to that of the independent variable.

Derivatives can be generalized to functions of several real variables. In this generalization, the derivative is reinterpreted as a linear transformation whose graph is (after an appropriate translation) the best linear approximation to the graph of the original function. The Jacobian matrix is the matrix that represents this linear transformation with respect to the basis given by the choice of independent and dependent variables. It can be calculated in terms of the partial derivatives with respect to the independent variables. For a real-valued function of several variables, the Jacobian matrix reduces to the gradient vector.

The process of finding a derivative is called differentiation. The reverse process is called antidifferentiation. The fundamental theorem of calculus relates antidifferentiation with integration. Differentiation and integration constitute the two fundamental operations in single-variable calculus.

Contents

Definition

A function of a real variable y = f(x) is differentiable at a point a of its domain, if its domain contains an open interval I containing a, and the limit

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle L=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}h }

exists. This means that, for every positive real number Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \varepsilon} (even very small), there exists a positive real number Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \delta} such that, for every h such that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |h| < \delta} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle h\ne 0} then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(a+h)} is defined, and

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \left|L-\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}h\right|<\varepsilon,}

where the vertical bars denote the absolute value (see (ε, δ)-definition of limit).

If the function f is differentiable at a, that is if the limit L exists, then this limit is called the derivative of f at a, and denoted Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(a)} (read as "f prime of a") or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\textstyle \frac{df}{dx}(a)} (read as "the derivative of f with respect to x at a", "dy by dx at a", or "dy over dx at a"); see Notation (details), below.

Explanations

Differentiation is the action of computing a derivative. The derivative of a function y = f(x) of a variable x is a measure of the rate at which the value y of the function changes with respect to the change of the variable x. It is called the derivative of f with respect to x. If x and y are real numbers, and if the graph of f is plotted against x, derivative is the slope of this graph at each point.

The simplest case, apart from the trivial case of a constant function, is when y is a linear function of x, meaning that the graph of y is a line. In this case, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y = f(x) = mx + b} , for real numbers m and b, and the slope m is given by

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m=\frac{\text{change in } y}{\text{change in } x} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x},}

where the symbol Δ (Delta) is an abbreviation for "change in", and the combinations Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta x} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta y} refer to corresponding changes, i.e.

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta y = f(x + \Delta x)- f(x)} .

The above formula holds because

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} y + \Delta y &= f\left( x+\Delta x\right)\\ &= m\left( x+\Delta x\right) +b =mx +m\Delta x +b \\ &= y + m\Delta x. \end{align} }

Thus

This gives the value for the slope of a line.

If the function f is not linear (i.e. its graph is not a straight line), then the change in y divided by the change in x varies over the considered range: differentiation is a method to find a unique value for this rate of change, not across a certain range Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (\Delta x),} but at any given value of x.

Figure 2. The secant to curve y= f(x) determined by points Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (x, f(x))} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (x + h, f(x + h))}

The idea, illustrated by Figures 1 to 3, is to compute the rate of change as the limit value of the ratio of the differences Δy / Δx as Δx tends towards 0.

Toward a definition

The most common approach to turn this intuitive idea into a precise definition is to define the derivative as a limit of difference quotients of real numbers. This is the approach described below.

Let f be a real valued function defined in an open neighborhood of a real number a. In classical geometry, the tangent line to the graph of the function f at a was the unique line through the point (a, f(a)) that did not meet the graph of f transversally, meaning that the line did not pass straight through the graph. The derivative of y with respect to x at a is, geometrically, the slope of the tangent line to the graph of f at (a, f(a)). The slope of the tangent line is very close to the slope of the line through (a, f(a)) and a nearby point on the graph, for example (a + h, f(a + h)). These lines are called secant lines. A value of h close to zero gives a good approximation to the slope of the tangent line, and smaller values (in absolute value) of h will, in general, give better approximations. The slope m of the secant line is the difference between the y values of these points divided by the difference between the x values, that is,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m = \frac{\Delta f(a)}{\Delta a} = \frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{(a+h)-(a)} = \frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}.}

This expression is Newton's difference quotient. Passing from an approximation to an exact answer is done using a limit. Geometrically, the limit of the secant lines is the tangent line. Therefore, the limit of the difference quotient as h approaches zero, if it exists, should represent the slope of the tangent line to (a, f(a)). This limit is defined to be the derivative of the function f at a:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(a)=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}.}

When the limit exists, f is said to be differentiable at a. Here f'(a) is one of several common notations for the derivative (see below). From this definition it is obvious that a differentiable function f is increasing if and only if its derivative is positive, and is decreasing if and only if its derivative is negative. This fact is used extensively when analyzing function behavior, e.g. when finding local extrema.

Equivalently, the derivative satisfies the property that

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(a+h) - (f(a) + f'(a)\cdot h)}{h} = 0,}

which has the intuitive interpretation (see Figure 1) that the tangent line to f at a gives the best linear approximation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(a+h) \approx f(a) + f'(a)h}

to f near a (i.e., for small h). This interpretation is the easiest to generalize to other settings (see below).

Substituting 0 for h in the difference quotient causes division by zero, so the slope of the tangent line cannot be found directly using this method. Instead, define Q(h) to be the difference quotient as a function of h:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle Q(h) = \frac{f(a + h) - f(a)}{h}.}

Q(h) is the slope of the secant line between (a, f(a)) and (a + h, f(a + h)). If f is a continuous function, meaning that its graph is an unbroken curve with no gaps, then Q is a continuous function away from h = 0. If the limit Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \lim_{h\to0} Q(h)} exists, meaning that there is a way of choosing a value for Q(0) that makes Q a continuous function, then the function f is differentiable at a, and its derivative at a equals Q(0).

In practice, the existence of a continuous extension of the difference quotient Q(h) to h = 0 is shown by modifying the numerator to cancel h in the denominator. Such manipulations can make the limit value of Q for small h clear even though Q is still not defined at h = 0. This process can be long and tedious for complicated functions, and many shortcuts are commonly used to simplify the process.

Example

The square function given by f(x) = x2 is differentiable at x = 3, and its derivative there is 6. This result is established by calculating the limit as h approaches zero of the difference quotient of f(3):

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} f'(3) & = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(3+h)-f(3)}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(3+h)^2 - 3^2}{h} \\[10pt] & = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{9 + 6h + h^2 - 9}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{6h + h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0}{(6 + h)}. \end{align} }

The last expression shows that the difference quotient equals 6 + h when h ≠ 0 and is undefined when h = 0, because of the definition of the difference quotient. However, the definition of the limit says the difference quotient does not need to be defined when h = 0. The limit is the result of letting h go to zero, meaning it is the value that 6 + h tends to as h becomes very small:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \lim_{h\to 0}{(6 + h)} = 6 + 0 = 6. }

Hence the slope of the graph of the square function at the point (3, 9) is 6, and so its derivative at x = 3 is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(3) = 6 } .

More generally, a similar computation shows that the derivative of the square function at x = a is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(a) = 2a} :

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} f'(a) & = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(a+h)^2 - a^2}{h} \\[0.3em] & = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{a^2 + 2ah + h^2 - a^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{2ah + h^2}{h} \\[0.3em] & = \lim_{h\to 0}{(2a + h)} = 2a \end{align}}

Continuity and differentiability

If f is differentiable at a, then f must also be continuous at a. As an example, choose a point a and let f be the step function that returns the value 1 for all x less than a, and returns a different value 10 for all x greater than or equal to a. f cannot have a derivative at a. If h is negative, then a + h is on the low part of the step, so the secant line from a to a + h is very steep, and as h tends to zero the slope tends to infinity. If h is positive, then a + h is on the high part of the step, so the secant line from a to a + h has slope zero. Consequently, the secant lines do not approach any single slope, so the limit of the difference quotient does not exist.

However, even if a function is continuous at a point, it may not be differentiable there. For example, the absolute value function given by f(x) = |x| is continuous at x = 0, but it is not differentiable there. If h is positive, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to h is one, whereas if h is negative, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to h is negative one. This can be seen graphically as a "kink" or a "cusp" in the graph at x = 0. Even a function with a smooth graph is not differentiable at a point where its tangent is vertical: For instance, the function given by f(x) = x1/3 is not differentiable at x = 0.

In summary, a function that has a derivative is continuous, but there are continuous functions that do not have a derivative.

Most functions that occur in practice have derivatives at all points or at almost every point. Early in the history of calculus, many mathematicians assumed that a continuous function was differentiable at most points. Under mild conditions, for example if the function is a monotone function or a Lipschitz function, this is true. However, in 1872 Weierstrass found the first example of a function that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere. This example is now known as the Weierstrass function. In 1931, Stefan Banach proved that the set of functions that have a derivative at some point is a meager set in the space of all continuous functions. Informally, this means that hardly any random continuous functions have a derivative at even one point.

Derivative as a function

Let f be a function that has a derivative at every point in its domain. We can then define a function that maps every point x to the value of the derivative of f at x. This function is written Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'} and is called the derivative function or the derivative of f.

Sometimes f has a derivative at most, but not all, points of its domain. The function whose value at a equals Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(a)} whenever Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(a)} is defined and elsewhere is undefined is also called the derivative of f. It is still a function, but its domain is strictly smaller than the domain of f.

Using this idea, differentiation becomes a function of functions: The derivative is an operator whose domain is the set of all functions that have derivatives at every point of their domain and whose range is a set of functions. If we denote this operator by D, then D(f) is the function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'} . Since D(f) is a function, it can be evaluated at a point a. By the definition of the derivative function, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D(f)(a) = f'(a)} .

For comparison, consider the doubling function given by f(x) = 2x; f is a real-valued function of a real number, meaning that it takes numbers as inputs and has numbers as outputs:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} 1 &{}\mapsto 2,\\ 2 &{}\mapsto 4,\\ 3 &{}\mapsto 6. \end{align}}

The operator D, however, is not defined on individual numbers. It is only defined on functions:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} D(x \mapsto 1) &= (x \mapsto 0),\\ D(x \mapsto x) &= (x \mapsto 1),\\ D\left(x \mapsto x^2\right) &= (x \mapsto 2\cdot x). \end{align}}

Because the output of D is a function, the output of D can be evaluated at a point. For instance, when D is applied to the square function, x ↦ x2, D outputs the doubling function x ↦ 2x, which we named f(x). This output function can then be evaluated to get f(1) = 2, f(2) = 4, and so on.

Higher derivatives

Let f be a differentiable function, and let f ′ be its derivative. The derivative of f ′ (if it has one) is written f ′′ and is called the second derivative of f. Similarly, the derivative of the second derivative, if it exists, is written f ′′′ and is called the third derivative of f. Continuing this process, one can define, if it exists, the nth derivative as the derivative of the (n−1)th derivative. These repeated derivatives are called higher-order derivatives. The nth derivative is also called the derivative of order n.

If x(t) represents the position of an object at time t, then the higher-order derivatives of x have specific interpretations in physics. The first derivative of x is the object's velocity. The second derivative of x is the acceleration. The third derivative of x is the jerk. And finally, the fourth through sixth derivatives of x are snap, crackle, and pop; most applicable to astrophysics.

A function f need not have a derivative (for example, if it is not continuous). Similarly, even if f does have a derivative, it may not have a second derivative. For example, let

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x) = \begin{cases} +x^2, & \text{if }x\ge 0 \\ -x^2, & \text{if }x \le 0.\end{cases}}

Calculation shows that f is a differentiable function whose derivative at Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x} is given by

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(x) = \begin{cases} +2x, & \text{if }x\ge 0 \\ -2x, & \text{if }x \le 0.\end{cases}}

f'(x) is twice the absolute value function at Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x} , and it does not have a derivative at zero. Similar examples show that a function can have a kth derivative for each non-negative integer k but not a (k + 1)th derivative. A function that has k successive derivatives is called k times differentiable. If in addition the kth derivative is continuous, then the function is said to be of differentiability class Ck. (This is a stronger condition than having k derivatives.) A function that has infinitely many derivatives is called infinitely differentiable or smooth.

On the real line, every polynomial function is infinitely differentiable. By standard differentiation rules, if a polynomial of degree n is differentiated n times, then it becomes a constant function. All of its subsequent derivatives are identically zero. In particular, they exist, so polynomials are smooth functions.

The derivatives of a function f at a point x provide polynomial approximations to that function near x. For example, if f is twice differentiable, then

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x+h) \approx f(x) + f'(x)h + \tfrac{1}{2} f''(x) h^2}

in the sense that

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x) - f'(x)h - \frac{1}{2} f''(x) h^2}{h^2} = 0.}

If f is infinitely differentiable, then this is the beginning of the Taylor series for f evaluated at x + h around x.

Inflection point

A point where the second derivative of a function changes sign is called an inflection point. At an inflection point, the second derivative may be zero, as in the case of the inflection point x = 0 of the function given by Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x) = x^3} , or it may fail to exist, as in the case of the inflection point x = 0 of the function given by Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x) = x^\frac{1}{3}} . At an inflection point, a function switches from being a convex function to being a concave function or vice versa.

Notation (details)

Leibniz's notation

The symbols Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle dx} , Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle dy} , and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{dy}{dx}} were introduced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1675. It is still commonly used when the equation y = f(x) is viewed as a functional relationship between dependent and independent variables. Then the first derivative is denoted by

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{dy}{dx},\quad\frac{d f}{dx}, \text{ or }\frac{d}{dx}f,}

and was once thought of as an infinitesimal quotient. Higher derivatives are expressed using the notation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d^ny}{dx^n}, \quad\frac{d^n f}{dx^n}, \text{ or } \frac{d^n}{dx^n}f}

for the nth derivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y = f(x)} . These are abbreviations for multiple applications of the derivative operator. For example,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} = \frac{d}{dx}\left(\frac{dy}{dx}\right).}

With Leibniz's notation, we can write the derivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y} at the point Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x = a} in two different ways:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \left.\frac{dy}{dx}\right|_{x=a} = \frac{dy}{dx}(a).}

Leibniz's notation allows one to specify the variable for differentiation (in the denominator), which is relevant in partial differentiation. It also can be used to write the chain rule as

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \cdot \frac{du}{dx}.}

Lagrange's notation

Sometimes referred to as prime notation, one of the most common modern notation for differentiation is due to Joseph-Louis Lagrange and uses the prime mark, so that the derivative of a function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f} is denoted Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'} . Similarly, the second and third derivatives are denoted

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (f')'=f''} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (f'')'=f'''.}

To denote the number of derivatives beyond this point, some authors use Roman numerals in superscript, whereas others place the number in parentheses:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f^{\mathrm{iv}}} or

The latter notation generalizes to yield the notation Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f^{(n)}} for the nth derivative of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f} – this notation is most useful when we wish to talk about the derivative as being a function itself, as in this case the Leibniz notation can become cumbersome.

Newton's notation

Newton's notation for differentiation, also called the dot notation, places a dot over the function name to represent a time derivative. If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y = f(t)} , then

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \dot{y}} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \ddot{y}}

denote, respectively, the first and second derivatives of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y} . This notation is used exclusively for derivatives with respect to time or arc length. It is typically used in differential equations in physics and differential geometry. The dot notation, however, becomes unmanageable for high-order derivatives (order 4 or more) and cannot deal with multiple independent variables.

Euler's notation

Euler's notation uses a differential operator Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D} , which is applied to a function Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f} to give the first derivative Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle Df} . The nth derivative is denoted Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D^nf} .

If y = f(x) is a dependent variable, then often the subscript x is attached to the D to clarify the independent variable x. Euler's notation is then written

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D_x y} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D_x f(x)} ,

although this subscript is often omitted when the variable x is understood, for instance when this is the only independent variable present in the expression.

Euler's notation is useful for stating and solving linear differential equations.

Rules of computation

The derivative of a function can, in principle, be computed from the definition by considering the difference quotient, and computing its limit. In practice, once the derivatives of a few simple functions are known, the derivatives of other functions are more easily computed using rules for obtaining derivatives of more complicated functions from simpler ones.

Rules for basic functions

Here are the rules for the derivatives of the most common basic functions, where a is a real number.

- Derivatives of powers:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}x^a = ax^{a-1}.}

- Exponential and logarithmic functions:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}e^x = e^x.}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}a^x = a^x\ln(a),\qquad a > 0}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\ln(x) = \frac{1}{x},\qquad x > 0.}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\log_a(x) = \frac{1}{x\ln(a)},\qquad x, a > 0}

- Trigonometric functions:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\sin(x) = \cos(x).}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\cos(x) = -\sin(x).}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\tan(x) = \sec^2(x) = \frac{1}{\cos^2(x)} = 1 + \tan^2(x).}

- Inverse trigonometric functions:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\arcsin(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}},\qquad -1<x<1.}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\arccos(x)= -\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}},\qquad -1<x<1.}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{d}{dx}\arctan(x)= \frac{1}{{1+x^2}}}

Rules for combined functions

Here are some of the most basic rules for deducing the derivative of a compound function from derivatives of basic functions.

- Constant rule: if f(x) is constant, then

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(x) = 0. }

- Sum rule:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (\alpha f + \beta g)' = \alpha f' + \beta g' } for all functions f and g and all real numbers Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \alpha} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \beta} .

- Product rule:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (fg)' = f 'g + fg' } for all functions f and g. As a special case, this rule includes the fact Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (\alpha f)' = \alpha f'} whenever Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \alpha} is a constant, because Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \alpha' f = 0 \cdot f = 0} by the constant rule.

- Quotient rule:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \left(\frac{f}{g} \right)' = \frac{f'g - fg'}{g^2}} for all functions f and g at all inputs where g ≠ 0.

- Chain rule for composite functions: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x) = h(g(x))}

, then

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f'(x) = h'(g(x)) \cdot g'(x). }

Computation example

The derivative of the function given by

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle f(x) = x^4 + \sin \left(x^2\right) - \ln(x) e^x + 7}

is

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} f'(x) &= 4 x^{(4-1)}+ \frac{d\left(x^2\right)}{dx}\cos \left(x^2\right) - \frac{d\left(\ln {x}\right)}{dx} e^x - \ln(x) \frac{d\left(e^x\right)}{dx} + 0 \\ &= 4x^3 + 2x\cos \left(x^2\right) - \frac{1}{x} e^x - \ln(x) e^x. \end{align} }

Here the second term was computed using the chain rule and third using the product rule. The known derivatives of the elementary functions x2, x4, sin(x), ln(x) and exp(x) = ex, as well as the constant 7, were also used.

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- Derivative, Wikipedia under a CC BY-SA license