Difference between revisions of "Absolute Value and the Real Line"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | == The Absolute Value of a Real Number == | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | :'''Definition:''' If <math>a</math> is a real number, then we define the '''absolute value of the number <math>a</math>''' denoted <math>\mid a \mid</math> or <math>\mathrm{abs}(a)</math> as: <math>\mid a \mid = \left\{\begin{matrix} a & \mathrm{if\,a>0,}\\ 0 & \mathrm{if\,a = 0,}\\ -a & \mathrm{if\,a <0.} \end{matrix}\right.</math>. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, suppose we want to find the absolute value of <math>5</math>. Well since <math>5 > 0</math>, we note that <math>\mid 5 \mid = 5</math>. If we wanted to find the absolute value of <math>-5</math> then since <math>-5 < 0</math> we note that <math>\mid -5 \mid = -(-5) = 5</math>. We will now look at some important properties of the absolute values of real numbers utilizing The Order Properties of Real Numbers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Theorem 1:''' If <math>a</math> is a real number then <math>\mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Proof:''' We will split this proof up into three cases. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 1:''' Suppose that <math>a > 0</math>. Then <math>-a < 0</math>. Therefore by the definition of the absolute value of a number, <math>\mid a \mid = a</math>, and <math>\mid -a \mid = -(-a) = a</math>, and so <math>\mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 2:''' Now suppose that <math>a = 0</math>. Therefore <math>-a = 0</math> and clearly <math>\mid a \mid = 0</math> and <math>\mid -a \mid = 0</math>, and so <math>\mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 3:''' Lastly suppose that <math>a < 0</math>. Then <math>-a > 0</math>. We obtain that <math>\mid a \mid = -a</math> and <math>\mid -a \mid = -a</math>, and so <math>\mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*In all three cases we get that <math>\mid a \mid = \mid a \mid</math>. <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Theorem 2:''' If <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are real numbers then <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Proof:''' We will split this proof up into three cases.</li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 1:''' Suppose that <math>a = 0</math> or <math>b = 0</math> or both <math>a, b = 0</math>. Then <math>a \cdot b = 0</math>, and so <math>\mid a b \mid = 0</math>. Similarly <math>\mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math> is either <math>0 \cdot \mid b \mid</math> or <math>\mid a \mid \cdot 0</math> or <math>0 \cdot 0</math>, all of which equal <math>0</math>, so <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 2:''' Suppose that <math>a, b > 0</math>. Then <math>ab > 0</math> and so <math>\mid ab \mid = ab</math> and <math>\mid a \mid \mid b \mid = ab</math>, so <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 3:''' Suppose that one of <math>a > 0</math> and <math>b < 0</math>. Then <math>ab < 0</math>. So <math>\mid ab \mid = -ab</math>, and <math>\mid a \mid \mid b \mid = a \cdot -b = -ab</math>, so <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Case 4:''' Suppose that <math>a, b < 0</math>. Then <math>ab > 0</math> and so <math>\mid ab \mid = ab</math> and <math>\mid a \mid \mid b \mid = -a \cdot -b = (-1)(-1)ab = ab</math>. So <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*In all four cases we get that <math>\mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid</math>. <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Theorem 3:''' If <math>a</math> is a real number then <math>\mid a \mid ^2 = a^2</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Proof:''' We know that <math>a^2 > 0</math> and there by applying Theorem 2 we get that <math>a^2 = \mid a^2 \mid = \mid a\cdot a \mid = \mid a \mid \mid a \mid = \mid a \mid ^2</math>. <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Theorem 4:''' If <math>c \geq 0</math> then <math>\mid a \mid \leq c</math> if and only if <math>-c \leq a \leq c</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*'''Proof:''' <math>\Rightarrow</math> If <math>\mid a \mid \leq c</math> then we have that both <math>a \leq c</math> and <math>-a \leq c</math> or rather <math>a \geq -c</math> which is equivalent to saying that <math>-c \leq a \leq c</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*<math>\Leftarrow</math> Suppose that <math>-c \leq a \leq c</math>. Then <math>a \leq c</math> and <math>-c \leq a \Leftrightarrow c \geq -a</math> so then <math>\mid a \mid \leq c</math>. <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Theorem 5:''' If <math>a</math> is a real number then <math>-\mid a \mid \leq a \leq \mid a \mid</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

== The Real Line == | == The Real Line == | ||

[[Image:Real number line.svg|thumb|right|382x382px|The real line]] | [[Image:Real number line.svg|thumb|right|382x382px|The real line]] | ||

| Line 32: | Line 84: | ||

===As a topological space=== | ===As a topological space=== | ||

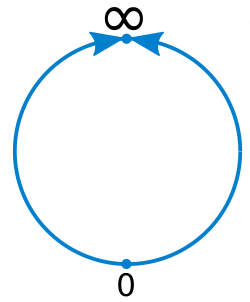

| − | [[Image:Real projective line.svg|right|thumb|150px|The real line can be | + | [[Image:Real projective line.svg|right|thumb|150px|The real line can be compactified by adding a point at infinity.]] |

The real line carries a standard topology, which can be introduced in two different, equivalent ways. First, since the real numbers are totally ordered, they carry an order topology. Second, the real numbers inherit a metric topology from the metric defined above. The order topology and metric topology on {{math|'''R'''}} are the same. As a topological space, the real line is homeomorphic to the open interval (0, 1). | The real line carries a standard topology, which can be introduced in two different, equivalent ways. First, since the real numbers are totally ordered, they carry an order topology. Second, the real numbers inherit a metric topology from the metric defined above. The order topology and metric topology on {{math|'''R'''}} are the same. As a topological space, the real line is homeomorphic to the open interval (0, 1). | ||

Latest revision as of 13:18, 27 November 2021

Contents

The Absolute Value of a Real Number

- Definition: If is a real number, then we define the absolute value of the number denoted or as: .

For example, suppose we want to find the absolute value of . Well since , we note that . If we wanted to find the absolute value of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -5} then since Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -5 < 0} we note that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid -5 \mid = -(-5) = 5} . We will now look at some important properties of the absolute values of real numbers utilizing The Order Properties of Real Numbers.

- Theorem 1: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} is a real number then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid} .

- Proof: We will split this proof up into three cases.

- Case 1: Suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a > 0} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -a < 0} . Therefore by the definition of the absolute value of a number, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = a} , and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid -a \mid = -(-a) = a} , and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid} .

- Case 2: Now suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a = 0} . Therefore Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -a = 0} and clearly Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = 0} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid -a \mid = 0} , and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid} .

- Case 3: Lastly suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a < 0} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -a > 0} . We obtain that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = -a} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid -a \mid = -a} , and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = \mid -a \mid} .

- In all three cases we get that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid = \mid a \mid} . Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \blacksquare}

- Theorem 2: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle b} are real numbers then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} .

- Proof: We will split this proof up into three cases.

- Case 1: Suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a = 0} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle b = 0} or both Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a, b = 0} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a \cdot b = 0} , and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a b \mid = 0} . Similarly Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} is either Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0 \cdot \mid b \mid} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \cdot 0} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0 \cdot 0} , all of which equal Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0} , so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} .

- Case 2: Suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a, b > 0} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle ab > 0} and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = ab} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \mid b \mid = ab} , so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} .

- Case 3: Suppose that one of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a > 0} and . Then . So Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = -ab} , and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \mid b \mid = a \cdot -b = -ab} , so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} .

- Case 4: Suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a, b < 0} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle ab > 0} and so Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = ab} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \mid b \mid = -a \cdot -b = (-1)(-1)ab = ab} . So Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} .

- In all four cases we get that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid ab \mid = \mid a \mid \mid b \mid} . Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \blacksquare}

- Theorem 3: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} is a real number then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid ^2 = a^2} .

- Proof: We know that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a^2 > 0} and there by applying Theorem 2 we get that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a^2 = \mid a^2 \mid = \mid a\cdot a \mid = \mid a \mid \mid a \mid = \mid a \mid ^2} . Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \blacksquare}

- Theorem 4: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle c \geq 0} then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \leq c} if and only if Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -c \leq a \leq c} .

- Proof: Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Rightarrow} If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \leq c} then we have that both Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a \leq c} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -a \leq c} or rather Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a \geq -c} which is equivalent to saying that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -c \leq a \leq c} .

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Leftarrow} Suppose that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -c \leq a \leq c} . Then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a \leq c} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -c \leq a \Leftrightarrow c \geq -a} so then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mid a \mid \leq c} . Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \blacksquare}

- Theorem 5: If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} is a real number then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -\mid a \mid \leq a \leq \mid a \mid} .

The Real Line

In mathematics, the real line, or real number line is the line whose points are the real numbers. That is, the real line is the set R of all real numbers, viewed as a geometric space, namely the Euclidean space of dimension one. It can be thought of as a vector space (or affine space), a metric space, a topological space, a measure space, or a linear continuum.

Just like the set of real numbers, the real line is usually denoted by the symbol R (or alternatively, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mathbb{R} } , the letter “R” in blackboard bold). However, it is sometimes denoted R1 in order to emphasize its role as the first Euclidean space.

This article focuses on the aspects of R as a geometric space in topology, geometry, and real analysis. The real numbers also play an important role in algebra as a field, but in this context R is rarely referred to as a line. For more information on R in all of its guises, see real number.

As a linear continuum

The real line is a linear continuum under the standard < ordering. Specifically, the real line is linearly ordered by <, and this ordering is dense and has the least-upper-bound property.

In addition to the above properties, the real line has no maximum or minimum element. It also has a countable dense subset, namely the set of rational numbers. It is a theorem that any linear continuum with a countable dense subset and no maximum or minimum element is order-isomorphic to the real line.

The real line also satisfies the countable chain condition: every collection of mutually disjoint, nonempty open intervals in R is countable. In order theory, the famous Suslin problem asks whether every linear continuum satisfying the countable chain condition that has no maximum or minimum element is necessarily order-isomorphic to R. This statement has been shown to be independent of the standard axiomatic system of set theory known as ZFC.

As a metric space

The real line forms a metric space, with the distance function given by absolute difference:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle d(x, y) = |x - y|.}

The metric tensor is clearly the 1-dimensional Euclidean metric. Since the n-dimensional Euclidean metric can be represented in matrix form as the n-by-n identity matrix, the metric on the real line is simply the 1-by-1 identity matrix, i.e. 1.

If p ∈ R and ε > 0, then the ε-ball in R centered at p is simply the open interval (p − ε, p + ε).

This real line has several important properties as a metric space:

- The real line is a complete metric space, in the sense that any Cauchy sequence of points converges.

- The real line is path-connected and is one of the simplest examples of a geodesic metric space.

- The Hausdorff dimension of the real line is equal to one.

As a topological space

The real line carries a standard topology, which can be introduced in two different, equivalent ways. First, since the real numbers are totally ordered, they carry an order topology. Second, the real numbers inherit a metric topology from the metric defined above. The order topology and metric topology on R are the same. As a topological space, the real line is homeomorphic to the open interval (0, 1).

The real line is trivially a topological manifold of dimension 1. Up to homeomorphism, it is one of only two different connected 1-manifolds without boundary, the other being the circle. It also has a standard differentiable structure on it, making it a differentiable manifold. (Up to diffeomorphism, there is only one differentiable structure that the topological space supports.)

The real line is a locally compact space and a paracompact space, as well as second-countable and normal. It is also path-connected, and is therefore connected as well, though it can be disconnected by removing any one point. The real line is also contractible, and as such all of its homotopy groups and reduced homology groups are zero.

As a locally compact space, the real line can be compactified in several different ways. The one-point compactification of R is a circle (namely, the real projective line), and the extra point can be thought of as an unsigned infinity. Alternatively, the real line has two ends, and the resulting end compactification is the extended real line [−∞, +∞]. There is also the Stone–Čech compactification of the real line, which involves adding an infinite number of additional points.

In some contexts, it is helpful to place other topologies on the set of real numbers, such as the lower limit topology or the Zariski topology. For the real numbers, the latter is the same as the finite complement topology.

As a vector space

The real line is a vector space over the field R of real numbers (that is, over itself) of dimension 1. It has the usual multiplication as an inner product, making it a Euclidean vector space. The norm defined by this inner product is simply the absolute value.

As a measure space

The real line carries a canonical measure, namely the Lebesgue measure. This measure can be defined as the completion of a Borel measure defined on R, where the measure of any interval is the length of the interval.

Lebesgue measure on the real line is one of the simplest examples of a Haar measure on a locally compact group.

In real algebras

The real line is a one-dimensional subspace of a real algebra A where R ⊂ A. For example, in the complex plane z = x + iy, the subspace {z : y = 0} is a real line. Similarly, the algebra of quaternions

- q = w + x i + y j + z k

has a real line in the subspace {q : x = y = z = 0 }.

When the real algebra is a direct sum Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A = R \oplus V,} then a conjugation on A is introduced by the mapping Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle v \mapsto -v} of subspace V. In this way the real line consists of the fixed points of the conjugation.

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- The Absolute Value of a Real Number, mathonline.wikidot.com under a CC BY-SA license

- Real line, Wikipedia under a CC BY-SA license