Difference between revisions of "Number Theory"

(Created page with "File:Spirale Ulam 150.jpg|thumb|250x250px|The distribution of prime numbers is a central point of study in number theory. This Ulam spiral serves to illustrate it, hinting,...") |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

====Dawn of arithmetic==== | ====Dawn of arithmetic==== | ||

[[Image:Plimpton 322.jpg|right|thumb|The Plimpton 322 tablet]] | [[Image:Plimpton 322.jpg|right|thumb|The Plimpton 322 tablet]] | ||

| − | The earliest historical find of an arithmetical nature is a fragment of a table: the broken clay tablet | + | The earliest historical find of an arithmetical nature is a fragment of a table: the broken clay tablet Plimpton 322 (Larsa, Mesopotamia, ca. 1800 BCE) contains a list of "Pythagorean triples", that is, integers <math>(a,b,c)</math> such that <math>a^2+b^2=c^2</math>. |

| − | The triples are too many and too large to have been obtained by | + | The triples are too many and too large to have been obtained by brute force. The heading over the first column reads: "The ''takiltum'' of the diagonal which has been subtracted such that the width..." |

| − | The table's layout suggests | + | The table's layout suggests that it was constructed by means of what amounts, in modern language, to the identity |

:<math>\left(\frac{1}{2} \left(x - \frac{1}{x}\right)\right)^2 + 1 = \left(\frac{1}{2} \left(x + \frac{1}{x} \right)\right)^2,</math> | :<math>\left(\frac{1}{2} \left(x - \frac{1}{x}\right)\right)^2 + 1 = \left(\frac{1}{2} \left(x + \frac{1}{x} \right)\right)^2,</math> | ||

| − | which is implicit in routine | + | which is implicit in routine Old Babylonian exercises. If some other method was used, the triples were first constructed and then reordered by <math>c/a</math>, presumably for actual use as a "table", for example, with a view to applications. |

| − | It is not known what these applications may have been, or whether there could have been any; | + | It is not known what these applications may have been, or whether there could have been any; Babylonian astronomy, for example, truly came into its own only later. It has been suggested instead that the table was a source of numerical examples for school problems. |

| − | |||

| − | While Babylonian number theory—or what survives of | + | While Babylonian number theory—or what survives of Babylonian mathematics that can be called thus—consists of this single, striking fragment, Babylonian algebra (in the secondary-school sense of "algebra") was exceptionally well developed. Late Neoplatonic sources state that Pythagoras learned mathematics from the Babylonians. Much earlier sources state that Thales and Pythagoras traveled and studied in Egypt. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Euclid IX 21–34 is very probably Pythagorean; it is very simple material ("odd times even is even", "if an odd number measures [= divides] an even number, then it also measures [= divides] half of it"), but it is all that is needed to prove that <math>\sqrt{2}</math> is irrational. Pythagorean mystics gave great importance to the odd and the even. | |

| − | is | + | The discovery that <math>\sqrt{2}</math> is irrational is credited to the early Pythagoreans (pre-Theodorus). By revealing (in modern terms) that numbers could be irrational, this discovery seems to have provoked the first foundational crisis in mathematical history; its proof or its divulgation are sometimes credited to Hippasus, who was expelled or split from the Pythagorean sect. This forced a distinction between ''numbers'' (integers and the rationals—the subjects of arithmetic), on the one hand, and ''lengths'' and ''proportions'' (which we would identify with real numbers, whether rational or not), on the other hand. |

| − | The discovery that <math>\sqrt{2}</math> is irrational is credited to the early Pythagoreans (pre- | ||

| − | |||

| − | The Pythagorean tradition spoke also of so-called | + | The Pythagorean tradition spoke also of so-called polygonal or figurate numbers. While square numbers, cubic numbers, etc., are seen now as more natural than triangular numbers, pentagonal numbers, etc., the study of the sums of triangular and pentagonal numbers would prove fruitful in the early modern period (17th to early 19th century). |

| − | We know of no clearly arithmetical material in | + | We know of no clearly arithmetical material in ancient Egyptian or Vedic sources, though there is some algebra in each. The Chinese remainder theorem appears as an exercise in ''Sunzi Suanjing'' (3rd, 4th or 5th century CE). (There is one important step glossed over in Sunzi's solution: it is the problem that was later solved by Āryabhaṭa's Kuṭṭaka – see below.) |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | There is also some numerical mysticism in Chinese mathematics, | + | There is also some numerical mysticism in Chinese mathematics, but, unlike that of the Pythagoreans, it seems to have led nowhere. Like the Pythagoreans' perfect numbers, magic squares have passed from superstition into recreation. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Classical Greece and the early Hellenistic period==== | ====Classical Greece and the early Hellenistic period==== | ||

| − | |||

| − | Aside from a few fragments, the mathematics of Classical Greece is known to us either through the reports of contemporary non-mathematicians or through mathematical works from the early Hellenistic period. | + | Aside from a few fragments, the mathematics of Classical Greece is known to us either through the reports of contemporary non-mathematicians or through mathematical works from the early Hellenistic period. In the case of number theory, this means, by and large, ''Plato'' and ''Euclid'', respectively. |

While Asian mathematics influenced Greek and Hellenistic learning, it seems to be the case that Greek mathematics is also an indigenous tradition. | While Asian mathematics influenced Greek and Hellenistic learning, it seems to be the case that Greek mathematics is also an indigenous tradition. | ||

| − | + | Eusebius, PE X, chapter 4 mentions of Pythagoras: | |

| − | <blockquote>"In fact the said Pythagoras, while busily studying the wisdom of each nation, visited Babylon, and Egypt, and all Persia, being instructed by the Magi and the priests: and in addition to these he is related to have studied under the Brahmans (these are Indian philosophers); and from some he gathered astrology, from others geometry, and arithmetic and music from others, and different things from different nations, and only from the wise men of Greece did he get nothing, wedded as they were to a poverty and dearth of wisdom: so on the contrary he himself became the author of instruction to the Greeks in the learning which he had procured from abroad." | + | <blockquote>"In fact the said Pythagoras, while busily studying the wisdom of each nation, visited Babylon, and Egypt, and all Persia, being instructed by the Magi and the priests: and in addition to these he is related to have studied under the Brahmans (these are Indian philosophers); and from some he gathered astrology, from others geometry, and arithmetic and music from others, and different things from different nations, and only from the wise men of Greece did he get nothing, wedded as they were to a poverty and dearth of wisdom: so on the contrary he himself became the author of instruction to the Greeks in the learning which he had procured from abroad."</blockquote> |

| − | Aristotle claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans, | + | Aristotle claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans, and Cicero repeats this claim: ''Platonem ferunt didicisse Pythagorea omnia'' ("They say Plato learned all things Pythagorean"). |

| − | + | Plato had a keen interest in mathematics, and distinguished clearly between arithmetic and calculation. (By ''arithmetic'' he meant, in part, theorising on number, rather than what ''arithmetic'' or ''number theory'' have come to mean.) It is through one of Plato's dialogues—namely, ''Theaetetus''—that we know that Theodorus had proven that <math>\sqrt{3}, \sqrt{5}, \dots, \sqrt{17}</math> are irrational. Theaetetus was, like Plato, a disciple of Theodorus's; he worked on distinguishing different kinds of incommensurables, and was thus arguably a pioneer in the study of number systems. (Book X of Euclid's Elements is described by Pappus as being largely based on Theaetetus's work.) | |

| − | + | Euclid devoted part of his ''Elements'' to prime numbers and divisibility, topics that belong unambiguously to number theory and are basic to it (Books VII to IX of Euclid's Elements). In particular, he gave an algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor of two numbers (the Euclidean algorithm; ''Elements'', Prop. VII.2) and the first known proof of the infinitude of primes (''Elements'', Prop. IX.20). | |

| − | In 1773, | + | In 1773, Lessing published an epigram he had found in a manuscript during his work as a librarian; it claimed to be a letter sent by Archimedes to Eratosthenes. The epigram proposed what has become known as Archimedes's cattle problem; its solution (absent from the manuscript) requires solving an indeterminate quadratic equation (which reduces to what would later be misnamed Pell's equation). As far as we know, such equations were first successfully treated by the Indian school. It is not known whether Archimedes himself had a method of solution. |

| − | |||

====Diophantus==== | ====Diophantus==== | ||

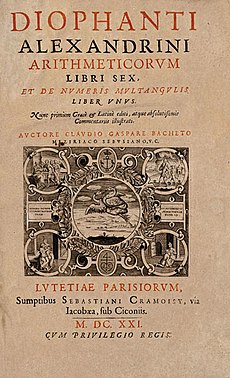

| − | [[Image:Diophantus-cover.jpg|thumb|upright|Title page of the 1621 edition of Diophantus's ''Arithmetica'', translated into | + | [[Image:Diophantus-cover.jpg|thumb|upright|Title page of the 1621 edition of Diophantus's ''Arithmetica'', translated into Latin by Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac.]] |

| − | Very little is known about | + | Very little is known about Diophantus of Alexandria; he probably lived in the third century CE, that is, about five hundred years after Euclid. Six out of the thirteen books of Diophantus's ''Arithmetica'' survive in the original Greek and four more survive in an Arabic translation. The ''Arithmetica'' is a collection of worked-out problems where the task is invariably to find rational solutions to a system of polynomial equations, usually of the form <math>f(x,y)=z^2</math> or <math>f(x,y,z)=w^2</math>. Thus, nowadays, we speak of ''Diophantine equations'' when we speak of polynomial equations to which rational or integer solutions must be found. |

| − | One may say that Diophantus was studying rational points, that is, points whose coordinates are rational—on | + | One may say that Diophantus was studying rational points, that is, points whose coordinates are rational—on curves and algebraic varieties; however, unlike the Greeks of the Classical period, who did what we would now call basic algebra in geometrical terms, Diophantus did what we would now call basic algebraic geometry in purely algebraic terms. In modern language, what Diophantus did was to find rational parametrizations of varieties; that is, given an equation of the form (say) |

| − | <math>f(x_1,x_2,x_3)=0</math>, his aim was to find (in essence) three | + | <math>f(x_1,x_2,x_3)=0</math>, his aim was to find (in essence) three rational functions <math>g_1, g_2, g_3</math> such that, for all values of <math>r</math> and <math>s</math>, setting |

<math>x_i = g_i(r,s)</math> for <math>i=1,2,3</math> gives a solution to <math>f(x_1,x_2,x_3)=0.</math> | <math>x_i = g_i(r,s)</math> for <math>i=1,2,3</math> gives a solution to <math>f(x_1,x_2,x_3)=0.</math> | ||

| − | Diophantus also studied the equations of some non-rational curves, for which no rational parametrisation is possible. He managed to find some rational points on these curves ( | + | Diophantus also studied the equations of some non-rational curves, for which no rational parametrisation is possible. He managed to find some rational points on these curves (elliptic curves, as it happens, in what seems to be their first known occurrence) by means of what amounts to a tangent construction: translated into coordinate geometry |

(which did not exist in Diophantus's time), his method would be visualised as drawing a tangent to a curve at a known rational point, and then finding the other point of intersection of the tangent with the curve; that other point is a new rational point. (Diophantus also resorted to what could be called a special case of a secant construction.) | (which did not exist in Diophantus's time), his method would be visualised as drawing a tangent to a curve at a known rational point, and then finding the other point of intersection of the tangent with the curve; that other point is a new rational point. (Diophantus also resorted to what could be called a special case of a secant construction.) | ||

| − | While Diophantus was concerned largely with rational solutions, he assumed some results on integer numbers, in particular that | + | While Diophantus was concerned largely with rational solutions, he assumed some results on integer numbers, in particular that every integer is the sum of four squares (though he never stated as much explicitly). |

====Āryabhaṭa, Brahmagupta, Bhāskara==== | ====Āryabhaṭa, Brahmagupta, Bhāskara==== | ||

| − | While Greek astronomy probably influenced Indian learning, to the point of introducing trigonometry, | + | While Greek astronomy probably influenced Indian learning, to the point of introducing trigonometry, it seems to be the case that Indian mathematics is otherwise an indigenous tradition; in particular, there is no evidence that Euclid's Elements reached India before the 18th century. |

| − | + | Āryabhaṭa (476–550 CE) showed that pairs of simultaneous congruences <math>n\equiv a_1 \bmod m_1</math>, <math>n\equiv a_2 \bmod m_2</math> could be solved by a method he called ''kuṭṭaka'', or ''pulveriser''; this is a procedure close to (a generalisation of) the Euclidean algorithm, which was probably discovered independently in India. Āryabhaṭa seems to have had in mind applications to astronomical calculations. | |

| − | + | Brahmagupta (628 CE) started the systematic study of indefinite quadratic equations—in particular, the misnamed Pell equation, in which Archimedes may have first been interested, and which did not start to be solved in the West until the time of Fermat and Euler. Later Sanskrit authors would follow, using Brahmagupta's technical terminology. A general procedure (the chakravala, or "cyclic method") for solving Pell's equation was finally found by Jayadeva (cited in the eleventh century; his work is otherwise lost); the earliest surviving exposition appears in Bhāskara II's Bīja-gaṇita (twelfth century). | |

| − | Indian mathematics remained largely unknown in Europe until the late eighteenth century; | + | Indian mathematics remained largely unknown in Europe until the late eighteenth century; Brahmagupta and Bhāskara's work was translated into English in 1817 by Henry Colebrooke. |

====Arithmetic in the Islamic golden age==== | ====Arithmetic in the Islamic golden age==== | ||

| − | |||

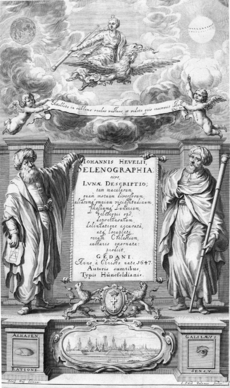

| − | [[File:Hevelius Selenographia frontispiece.png|upright|right|thumb| | + | [[File:Hevelius Selenographia frontispiece.png|upright|right|thumb|Al-Haytham as seen by the West: on the frontispiece of ''Selenographia'' Alhasen [sic] represents knowledge through reason and Galileo knowledge through the senses.]] |

| − | In the early ninth century, the caliph | + | In the early ninth century, the caliph Al-Ma'mun ordered translations of many Greek mathematical works and at least one Sanskrit work (the ''Sindhind'', |

| − | which may | + | which may be Brahmagupta's Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta). |

| − | + | Diophantus's main work, the ''Arithmetica'', was translated into Arabic by Qusta ibn Luqa (820–912). | |

| − | Diophantus's main work, the ''Arithmetica'', was translated into Arabic by | + | Part of the treatise ''al-Fakhri'' (by al-Karajī, 953 – ca. 1029) builds on it to some extent. According to Rashed Roshdi, Al-Karajī's contemporary Ibn al-Haytham knew what would later be called Wilson's theorem. |

| − | Part of the treatise ''al-Fakhri'' (by | ||

====Western Europe in the Middle Ages==== | ====Western Europe in the Middle Ages==== | ||

| − | Other than a treatise on squares in arithmetic progression by | + | Other than a treatise on squares in arithmetic progression by Fibonacci—who traveled and studied in north Africa and Constantinople—no number theory to speak of was done in western Europe during the Middle Ages. Matters started to change in Europe in the late Renaissance, thanks to a renewed study of the works of Greek antiquity. A catalyst was the textual emendation and translation into Latin of Diophantus' ''Arithmetica''. |

| − | |||

===Early modern number theory=== | ===Early modern number theory=== | ||

====Fermat==== | ====Fermat==== | ||

| − | [[Image:Pierre de Fermat.png|thumb|right|upright| | + | [[Image:Pierre de Fermat.png|thumb|right|upright|Pierre de Fermat]] |

| − | + | Pierre de Fermat (1607–1665) never published his writings; in particular, his work on number theory is contained almost entirely in letters to mathematicians and in private marginal notes. In his notes and letters, he scarcely wrote any proofs - he had no models in the area. | |

Over his lifetime, Fermat made the following contributions to the field: | Over his lifetime, Fermat made the following contributions to the field: | ||

| − | * One of Fermat's first interests was | + | * One of Fermat's first interests was perfect numbers (which appear in Euclid, ''Elements'' IX) and amicable numbers; these topics led him to work on integer divisors, which were from the beginning among the subjects of the correspondence (1636 onwards) that put him in touch with the mathematical community of the day. |

| − | * In 1638, Fermat claimed, without proof, that all whole numbers can be expressed as the sum of four squares or fewer. | + | * In 1638, Fermat claimed, without proof, that all whole numbers can be expressed as the sum of four squares or fewer. |

| − | * | + | * Fermat's little theorem (1640): if ''a'' is not divisible by a prime ''p'', then <math>a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p.</math> |

| − | + | * If ''a'' and ''b'' are coprime, then <math>a^2 + b^2</math> is not divisible by any prime congruent to −1 modulo 4; and every prime congruent to 1 modulo 4 can be written in the form <math>a^2 + b^2</math>. These two statements also date from 1640; in 1659, Fermat stated to Huygens that he had proven the latter statement by the method of infinite descent. | |

| − | * If ''a'' and ''b'' are coprime, then <math>a^2 + b^2</math> is not divisible by any prime congruent to −1 modulo 4; | + | * In 1657, Fermat posed the problem of solving <math>x^2 - N y^2 = 1</math> as a challenge to English mathematicians. The problem was solved in a few months by Wallis and Brouncker. Fermat considered their solution valid, but pointed out they had provided an algorithm without a proof (as had Jayadeva and Bhaskara, though Fermat wasn't aware of this). He stated that a proof could be found by infinite descent. |

| − | * In 1657, Fermat posed the problem of solving <math>x^2 - N y^2 = 1</math> as a challenge to English mathematicians. The problem was solved in a few months by Wallis and Brouncker. | + | * Fermat stated and proved (by infinite descent) in the appendix to ''Observations on Diophantus'' (Obs. XLV) that <math>x^{4} + y^{4} = z^{4}</math> has no non-trivial solutions in the integers. Fermat also mentioned to his correspondents that <math>x^3 + y^3 = z^3</math> has no non-trivial solutions, and that this could also be proven by infinite descent. The first known proof is due to Euler (1753; indeed by infinite descent). |

| − | * Fermat stated and proved (by infinite descent) in the appendix to ''Observations on Diophantus'' (Obs. XLV) | + | * Fermat claimed (Fermat's Last Theorem) to have shown there are no solutions to <math>x^n + y^n = z^n</math> for all <math>n\geq 3</math>; this claim appears in his annotations in the margins of his copy of Diophantus. |

| − | * Fermat claimed ( | ||

====Euler==== | ====Euler==== | ||

| − | [[Image:Leonhard Euler.jpg|thumb|upright| | + | [[Image:Leonhard Euler.jpg|thumb|upright|Leonhard Euler]] |

| − | The interest of | + | The interest of Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) in number theory was first spurred in 1729, when a friend of his, the amateur Goldbach, pointed him towards some of Fermat's work on the subject. This has been called the "rebirth" of modern number theory, after Fermat's relative lack of success in getting his contemporaries' attention for the subject. Euler's work on number theory includes the following: |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *''Proofs for Fermat's statements.'' This includes | + | *''Proofs for Fermat's statements.'' This includes Fermat's little theorem (generalised by Euler to non-prime moduli); the fact that <math>p = x^2 + y^2</math> if and only if <math>p\equiv 1 \bmod 4</math>; initial work towards a proof that every integer is the sum of four squares (the first complete proof is by Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1770), soon improved by Euler himself); the lack of non-zero integer solutions to <math>x^4 + y^4 = z^2</math> (implying the case ''n=4'' of Fermat's last theorem, the case ''n=3'' of which Euler also proved by a related method). |

| − | *'' | + | *''Pell's equation'', first misnamed by Euler. He wrote on the link between continued fractions and Pell's equation. |

| − | *''First steps towards | + | *''First steps towards analytic number theory.'' In his work of sums of four squares, partitions, pentagonal numbers, and the distribution of prime numbers, Euler pioneered the use of what can be seen as analysis (in particular, infinite series) in number theory. Since he lived before the development of complex analysis, most of his work is restricted to the formal manipulation of power series. He did, however, do some very notable (though not fully rigorous) early work on what would later be called the Riemann zeta function. |

| − | *''Quadratic forms''. Following Fermat's lead, Euler did further research on the question of which primes can be expressed in the form <math>x^2 + N y^2</math>, some of it prefiguring | + | *''Quadratic forms''. Following Fermat's lead, Euler did further research on the question of which primes can be expressed in the form <math>x^2 + N y^2</math>, some of it prefiguring quadratic reciprocity. |

| − | *''Diophantine equations''. Euler worked on some Diophantine equations of genus 0 and 1. | + | *''Diophantine equations''. Euler worked on some Diophantine equations of genus 0 and 1. In particular, he studied Diophantus's work; he tried to systematise it, but the time was not yet ripe for such an endeavour—algebraic geometry was still in its infancy. He did notice there was a connection between Diophantine problems and elliptic integrals, whose study he had himself initiated. |

| − | [[File:Andrew wiles1-3.jpg|thumb|upright|"Here was a problem, that I, a 10 year old, could understand, and I knew from that moment that I would never let it go. I had to solve it." | + | [[File:Andrew wiles1-3.jpg|thumb|upright|"Here was a problem, that I, a 10 year old, could understand, and I knew from that moment that I would never let it go. I had to solve it." – Sir Andrew Wiles about his proof of Fermat's Last Theorem.]] |

====Lagrange, Legendre, and Gauss==== | ====Lagrange, Legendre, and Gauss==== | ||

| − | [[Image:Disqvisitiones-800.jpg|upright|150px|thumb| | + | [[Image:Disqvisitiones-800.jpg|upright|150px|thumb|Carl Friedrich Gauss's Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, first edition]] |

| − | + | Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) was the first to give full proofs of some of Fermat's and Euler's work and observations—for instance, the four-square theorem and the basic theory of the misnamed "Pell's equation" (for which an algorithmic solution was found by Fermat and his contemporaries, and also by Jayadeva and Bhaskara II before them.) He also studied quadratic forms in full generality (as opposed to <math>m X^2 + n Y^2</math>)—defining their equivalence relation, showing how to put them in reduced form, etc. | |

| − | + | Adrien-Marie Legendre (1752–1833) was the first to state the law of quadratic reciprocity. He also | |

| − | conjectured what amounts to the | + | conjectured what amounts to the prime number theorem and Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions. He gave a full treatment of the equation <math>a x^2 + b y^2 + c z^2 = 0</math> and worked on quadratic forms along the lines later developed fully by Gauss. In his old age, he was the first to prove Fermat's Last Theorem for <math>n=5</math> (completing work by Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, and crediting both him and Sophie Germain). |

[[File:Carl Friedrich Gauss.jpg|thumb|left|Carl Friedrich Gauss]] | [[File:Carl Friedrich Gauss.jpg|thumb|left|Carl Friedrich Gauss]] | ||

| − | In his '' | + | In his ''Disquisitiones Arithmeticae'' (1798), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) proved the law of quadratic reciprocity and developed the theory of quadratic forms (in particular, defining their composition). He also introduced some basic notation (congruences) and devoted a section to computational matters, including primality tests. The last section of the ''Disquisitiones'' established a link between roots of unity and number theory: |

<blockquote>The theory of the division of the circle...which is treated in sec. 7 does not belong | <blockquote>The theory of the division of the circle...which is treated in sec. 7 does not belong | ||

| − | by itself to arithmetic, but its principles can only be drawn from higher arithmetic. | + | by itself to arithmetic, but its principles can only be drawn from higher arithmetic.</blockquote> |

| − | In this way, Gauss arguably made a first foray towards both | + | In this way, Gauss arguably made a first foray towards both Évariste Galois's work and algebraic number theory. |

===Maturity and division into subfields=== | ===Maturity and division into subfields=== | ||

| − | [[Image:ErnstKummer.jpg|upright|thumb| | + | [[Image:ErnstKummer.jpg|upright|thumb|Ernst Kummer]] |

| − | [[Image:Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet.jpg|upright|left|thumb| | + | [[Image:Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet.jpg|upright|left|thumb|Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet]] |

Starting early in the nineteenth century, the following developments gradually took place: | Starting early in the nineteenth century, the following developments gradually took place: | ||

| − | * The rise to self-consciousness of number theory (or ''higher arithmetic'') as a field of study. | + | * The rise to self-consciousness of number theory (or ''higher arithmetic'') as a field of study. |

| − | * The development of much of modern mathematics necessary for basic modern number theory: | + | * The development of much of modern mathematics necessary for basic modern number theory: complex analysis, group theory, Galois theory—accompanied by greater rigor in analysis and abstraction in algebra. |

| − | * The rough subdivision of number theory into its modern subfields—in particular, | + | * The rough subdivision of number theory into its modern subfields—in particular, analytic and algebraic number theory. |

| − | Algebraic number theory may be said to start with the study of reciprocity and | + | Algebraic number theory may be said to start with the study of reciprocity and cyclotomy, but truly came into its own with the development of abstract algebra and early ideal theory and valuation theory; see below. A conventional starting point for analytic number theory is Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions (1837), whose proof introduced L-functions and involved some asymptotic analysis and a limiting process on a real variable. The first use of analytic ideas in number theory actually |

| − | goes back to Euler (1730s), | + | goes back to Euler (1730s), who used formal power series and non-rigorous (or implicit) limiting arguments. The use of ''complex'' analysis in number theory comes later: the work of Bernhard Riemann (1859) on the zeta function is the canonical starting point; Jacobi's four-square theorem (1839), which predates it, belongs to an initially different strand that has by now taken a leading role in analytic number theory (modular forms). |

The history of each subfield is briefly addressed in its own section below; see the main article of each subfield for fuller treatments. Many of the most interesting questions in each area remain open and are being actively worked on. | The history of each subfield is briefly addressed in its own section below; see the main article of each subfield for fuller treatments. Many of the most interesting questions in each area remain open and are being actively worked on. | ||

| Line 164: | Line 146: | ||

==Main subdivisions== | ==Main subdivisions== | ||

===Elementary number theory=== | ===Elementary number theory=== | ||

| − | The term '' | + | The term ''elementary'' generally denotes a method that does not use complex analysis. For example, the prime number theorem was first proven using complex analysis in 1896, but an elementary proof was found only in 1949 by Erdős and Selberg. The term is somewhat ambiguous: for example, proofs based on complex Tauberian theorems (for example, Wiener–Ikehara) are often seen as quite enlightening but not elementary, in spite of using Fourier analysis, rather than complex analysis as such. Here as elsewhere, an ''elementary'' proof may be longer and more difficult for most readers than a non-elementary one. |

| − | [[File:Paul Erdos with Terence Tao.jpg|thumb|270px|Number theorists | + | [[File:Paul Erdos with Terence Tao.jpg|thumb|270px|Number theorists Paul Erdős and Terence Tao in 1985, when Erdős was 72 and Tao was 10.]] |

| − | Number theory has the reputation of being a field many of whose results can be stated to the layperson. At the same time, the proofs of these results are not particularly accessible, in part because the range of tools they use is, if anything, unusually broad within mathematics. | + | Number theory has the reputation of being a field many of whose results can be stated to the layperson. At the same time, the proofs of these results are not particularly accessible, in part because the range of tools they use is, if anything, unusually broad within mathematics. |

===Analytic number theory=== | ===Analytic number theory=== | ||

| − | |||

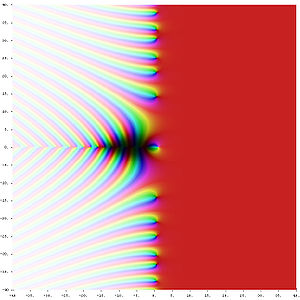

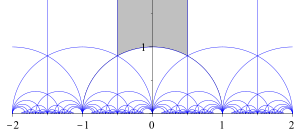

| − | [[Image:Complex zeta.jpg|right|thumb| | + | [[Image:Complex zeta.jpg|right|thumb|Riemann zeta function ζ(''s'') in the complex plane. The color of a point ''s'' gives the value of ζ(''s''): dark colors denote values close to zero and hue gives the value's argument.]] |

| − | [[File:ModularGroup-FundamentalDomain.svg|thumb|The action of the | + | [[File:ModularGroup-FundamentalDomain.svg|thumb|The action of the modular group on the upper half plane. The region in grey is the standard fundamental domain.]] |

''Analytic number theory'' may be defined | ''Analytic number theory'' may be defined | ||

| − | * in terms of its tools, as the study of the integers by means of tools from real and complex analysis; | + | * in terms of its tools, as the study of the integers by means of tools from real and complex analysis; or |

| − | * in terms of its concerns, as the study within number theory of estimates on size and density, as opposed to identities. | + | * in terms of its concerns, as the study within number theory of estimates on size and density, as opposed to identities. |

| − | Some subjects generally considered to be part of analytic number theory, for example, | + | Some subjects generally considered to be part of analytic number theory, for example, sieve theory, are better covered by the second rather than the first definition: some of sieve theory, for instance, uses little analysis, yet it does belong to analytic number theory. |

| − | The following are examples of problems in analytic number theory: the | + | The following are examples of problems in analytic number theory: the prime number theorem, the Goldbach conjecture (or the twin prime conjecture, or the Hardy–Littlewood conjectures), the Waring problem and the Riemann hypothesis. Some of the most important tools of analytic number theory are the circle method, sieve methods and L-functions (or, rather, the study of their properties). The theory of modular forms (and, more generally, automorphic forms) also occupies an increasingly central place in the toolbox of analytic number theory. |

| − | One may ask analytic questions about | + | One may ask analytic questions about algebraic numbers, and use analytic means to answer such questions; it is thus that algebraic and analytic number theory intersect. For example, one may define prime ideals (generalizations of prime numbers in the field of algebraic numbers) and ask how many prime ideals there are up to a certain size. This question can be answered by means of an examination of Dedekind zeta functions, which are generalizations of the Riemann zeta function, a key analytic object at the roots of the subject.[81] This is an example of a general procedure in analytic number theory: deriving information about the distribution of a sequence (here, prime ideals or prime numbers) from the analytic behavior of an appropriately constructed complex-valued function. |

===Algebraic number theory=== | ===Algebraic number theory=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | An ''algebraic number'' is any complex number that is a solution to some polynomial equation <math>f(x)=0</math> with rational coefficients; for example, every solution <math>x</math> of <math>x^5 + (11/2) x^3 - 7 x^2 + 9 = 0 </math> (say) is an algebraic number. Fields of algebraic numbers are also called '' | + | An ''algebraic number'' is any complex number that is a solution to some polynomial equation <math>f(x)=0</math> with rational coefficients; for example, every solution <math>x</math> of <math>x^5 + (11/2) x^3 - 7 x^2 + 9 = 0 </math> (say) is an algebraic number. Fields of algebraic numbers are also called ''algebraic number fields'', or shortly ''number fields''. Algebraic number theory studies algebraic number fields. Thus, analytic and algebraic number theory can and do overlap: the former is defined by its methods, the latter by its objects of study. |

| − | It could be argued that the simplest kind of number fields (viz., quadratic fields) were already studied by Gauss, as the discussion of quadratic forms in ''Disquisitiones arithmeticae'' can be restated in terms of | + | It could be argued that the simplest kind of number fields (viz., quadratic fields) were already studied by Gauss, as the discussion of quadratic forms in ''Disquisitiones arithmeticae'' can be restated in terms of ideals and norms in quadratic fields. (A ''quadratic field'' consists of all |

| − | |||

numbers of the form <math> a + b \sqrt{d}</math>, where | numbers of the form <math> a + b \sqrt{d}</math>, where | ||

<math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are rational numbers and <math>d</math> | <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are rational numbers and <math>d</math> | ||

is a fixed rational number whose square root is not rational.) | is a fixed rational number whose square root is not rational.) | ||

| − | For that matter, the 11th-century | + | For that matter, the 11th-century chakravala method amounts—in modern terms—to an algorithm for finding the units of a real quadratic number field. However, neither Bhāskara nor Gauss knew of number fields as such. |

The grounds of the subject as we know it were set in the late nineteenth century, when ''ideal numbers'', the ''theory of ideals'' and ''valuation theory'' were developed; these are three complementary ways of dealing with the lack of unique factorisation in algebraic number fields. (For example, in the field generated by the rationals | The grounds of the subject as we know it were set in the late nineteenth century, when ''ideal numbers'', the ''theory of ideals'' and ''valuation theory'' were developed; these are three complementary ways of dealing with the lack of unique factorisation in algebraic number fields. (For example, in the field generated by the rationals | ||

| Line 201: | Line 180: | ||

<math> 6 = (1 + \sqrt{-5}) ( 1 - \sqrt{-5})</math>; all of <math>2</math>, <math>3</math>, <math>1 + \sqrt{-5}</math> and | <math> 6 = (1 + \sqrt{-5}) ( 1 - \sqrt{-5})</math>; all of <math>2</math>, <math>3</math>, <math>1 + \sqrt{-5}</math> and | ||

<math> 1 - \sqrt{-5}</math> | <math> 1 - \sqrt{-5}</math> | ||

| − | are irreducible, and thus, in a naïve sense, analogous to primes among the integers.) The initial impetus for the development of ideal numbers (by | + | are irreducible, and thus, in a naïve sense, analogous to primes among the integers.) The initial impetus for the development of ideal numbers (by Kummer) seems to have come from the study of higher reciprocity laws, that is, generalisations of quadratic reciprocity. |

Number fields are often studied as extensions of smaller number fields: a field ''L'' is said to be an ''extension'' of a field ''K'' if ''L'' contains ''K''. | Number fields are often studied as extensions of smaller number fields: a field ''L'' is said to be an ''extension'' of a field ''K'' if ''L'' contains ''K''. | ||

(For example, the complex numbers ''C'' are an extension of the reals ''R'', and the reals ''R'' are an extension of the rationals ''Q''.) | (For example, the complex numbers ''C'' are an extension of the reals ''R'', and the reals ''R'' are an extension of the rationals ''Q''.) | ||

| − | Classifying the possible extensions of a given number field is a difficult and partially open problem. Abelian extensions—that is, extensions ''L'' of ''K'' such that the | + | Classifying the possible extensions of a given number field is a difficult and partially open problem. Abelian extensions—that is, extensions ''L'' of ''K'' such that the Galois group Gal(''L''/''K'') of ''L'' over ''K'' is an abelian group—are relatively well understood. |

| − | + | Their classification was the object of the programme of class field theory, which was initiated in the late 19th century (partly by Kronecker and Eisenstein) and carried out largely in 1900–1950. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Their classification was the object of the programme of | ||

| − | An example of an active area of research in algebraic number theory is | + | An example of an active area of research in algebraic number theory is Iwasawa theory. The Langlands program, one of the main current large-scale research plans in mathematics, is sometimes described as an attempt to generalise class field theory to non-abelian extensions of number fields. |

===Diophantine geometry=== | ===Diophantine geometry=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | The central problem of ''Diophantine geometry'' is to determine when a | + | The central problem of ''Diophantine geometry'' is to determine when a Diophantine equation has solutions, and if it does, how many. The approach taken is to think of the solutions of an equation as a geometric object. |

| − | For example, an equation in two variables defines a curve in the plane. More generally, an equation, or system of equations, in two or more variables defines a | + | For example, an equation in two variables defines a curve in the plane. More generally, an equation, or system of equations, in two or more variables defines a curve, a surface or some other such object in ''n''-dimensional space. In Diophantine geometry, one asks whether there are any ''rational points'' (points all of whose coordinates are rationals) or |

''integral points'' (points all of whose coordinates are integers) on the curve or surface. If there are any such points, the next step is to ask how many there are and how they are distributed. A basic question in this direction is if there are finitely | ''integral points'' (points all of whose coordinates are integers) on the curve or surface. If there are any such points, the next step is to ask how many there are and how they are distributed. A basic question in this direction is if there are finitely | ||

or infinitely many rational points on a given curve (or surface). | or infinitely many rational points on a given curve (or surface). | ||

| − | In the | + | In the Pythagorean equation <math>x^2+y^2 = 1,</math> |

we would like to study its rational solutions, that is, its solutions | we would like to study its rational solutions, that is, its solutions | ||

<math>(x,y)</math> such that | <math>(x,y)</math> such that | ||

| Line 235: | Line 206: | ||

described by <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math>. (This curve happens to be a circle of radius 1 around the origin.) | described by <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math>. (This curve happens to be a circle of radius 1 around the origin.) | ||

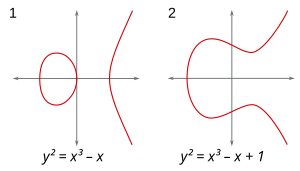

| − | [[Image:ECClines-3.svg|right|thumb|300px|Two examples of an | + | [[Image:ECClines-3.svg|right|thumb|300px|Two examples of an elliptic curve, that is, a curve |

| − | of genus 1 having at least one rational point. (Either graph can be seen as a slice of a | + | of genus 1 having at least one rational point. (Either graph can be seen as a slice of a torus in four-dimensional space.)]] |

| − | The rephrasing of questions on equations in terms of points on curves turns out to be felicitous. The finiteness or not of the number of rational or integer points on an algebraic curve—that is, rational or integer solutions to an equation <math>f(x,y)=0</math>, where <math>f</math> is a polynomial in two variables—turns out to depend crucially on the ''genus'' of the curve. The ''genus'' can be defined as follows: | + | The rephrasing of questions on equations in terms of points on curves turns out to be felicitous. The finiteness or not of the number of rational or integer points on an algebraic curve—that is, rational or integer solutions to an equation <math>f(x,y)=0</math>, where <math>f</math> is a polynomial in two variables—turns out to depend crucially on the ''genus'' of the curve. The ''genus'' can be defined as follows: allow the variables in <math>f(x,y)=0</math> to be complex numbers; then <math>f(x,y)=0</math> defines a 2-dimensional surface in (projective) 4-dimensional space (since two complex variables can be decomposed into four real variables, that is, four dimensions). If we count the number of (doughnut) holes in the surface; we call this number the ''genus'' of <math>f(x,y)=0</math>. Other geometrical notions turn out to be just as crucial. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | There is also the closely linked area of | + | There is also the closely linked area of Diophantine approximations: given a number <math>x</math>, then finding how well can it be approximated by rationals. (We are looking for approximations that are good relative to the amount of space that it takes to write the rational: call <math>a/q</math> (with <math>\gcd(a,q)=1</math>) a good approximation to <math>x</math> if <math>|x-a/q|<\frac{1}{q^c}</math>, where <math>c</math> is large.) This question is of special interest if <math>x</math> is an algebraic number. If <math>x</math> cannot be well approximated, then some equations do not have integer or rational solutions. Moreover, several concepts (especially that of height) turn out to be critical both in Diophantine geometry and in the study of Diophantine approximations. This question is also of special interest in transcendental number theory: if a number can be better approximated than any algebraic number, then it is a transcendental number. It is by this argument that <math< \pi </math> and e have been shown to be transcendental. |

| − | Diophantine geometry should not be confused with the | + | Diophantine geometry should not be confused with the geometry of numbers, which is a collection of graphical methods for answering certain questions in algebraic number theory. ''Arithmetic geometry'', however, is a contemporary term |

for much the same domain as that covered by the term ''Diophantine geometry''. The term ''arithmetic geometry'' is arguably used | for much the same domain as that covered by the term ''Diophantine geometry''. The term ''arithmetic geometry'' is arguably used | ||

| − | most often when one wishes to emphasise the connections to modern algebraic geometry (as in, for instance, | + | most often when one wishes to emphasise the connections to modern algebraic geometry (as in, for instance, Faltings's theorem) rather than to techniques in Diophantine approximations. |

==Other subfields== | ==Other subfields== | ||

| − | The areas below date from no earlier than the mid-twentieth century, even if they are based on older material. For example, as is explained below, the matter of algorithms in number theory is very old, in some sense older than the concept of proof; at the same time, the modern study of | + | The areas below date from no earlier than the mid-twentieth century, even if they are based on older material. For example, as is explained below, the matter of algorithms in number theory is very old, in some sense older than the concept of proof; at the same time, the modern study of computability dates only from the 1930s and 1940s, and computational complexity theory from the 1970s. |

===Probabilistic number theory=== | ===Probabilistic number theory=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | Much of probabilistic number theory can be seen as an important special case of the study of variables that are almost, but not quite, mutually | + | Much of probabilistic number theory can be seen as an important special case of the study of variables that are almost, but not quite, mutually independent. For example, the event that a random integer between one and a million be divisible by two and the event that it be divisible by three are almost independent, but not quite. |

| − | It is sometimes said that | + | It is sometimes said that probabilistic combinatorics uses the fact that whatever happens with probability greater than <math>0</math> must happen sometimes; one may say with equal justice that many applications of probabilistic number theory hinge on the fact that whatever is unusual must be rare. If certain algebraic objects (say, rational or integer solutions to certain equations) can be shown to be in the tail of certain sensibly defined distributions, it follows that there must be few of them; this is a very concrete non-probabilistic statement following from a probabilistic one. |

| − | At times, a non-rigorous, probabilistic approach leads to a number of | + | At times, a non-rigorous, probabilistic approach leads to a number of heuristic algorithms and open problems, notably Cramér's conjecture. |

===Arithmetic combinatorics=== | ===Arithmetic combinatorics=== | ||

| − | |||

If we begin from a fairly "thick" infinite set <math>A</math>, does it contain many elements in arithmetic progression: <math>a</math>, | If we begin from a fairly "thick" infinite set <math>A</math>, does it contain many elements in arithmetic progression: <math>a</math>, | ||

<math>a+b, a+2 b, a+3 b, \ldots, a+10b</math>, say? Should it be possible to write large integers as sums of elements of <math>A</math>? | <math>a+b, a+2 b, a+3 b, \ldots, a+10b</math>, say? Should it be possible to write large integers as sums of elements of <math>A</math>? | ||

| − | These questions are characteristic of ''arithmetic combinatorics''. This is a presently coalescing field; it subsumes '' | + | These questions are characteristic of ''arithmetic combinatorics''. This is a presently coalescing field; it subsumes ''additive number theory'' (which concerns itself with certain very specific sets <math>A</math> of arithmetic significance, such as the primes or the squares) and, arguably, some of the ''geometry of numbers'', |

| − | together with some rapidly developing new material. Its focus on issues of growth and distribution accounts in part for its developing links with | + | together with some rapidly developing new material. Its focus on issues of growth and distribution accounts in part for its developing links with ergodic theory, finite group theory, model theory, and other fields. The term ''additive combinatorics'' is also used; however, the sets <math>A</math> being studied need not be sets of integers, but rather subsets of non-commutative groups, for which the multiplication symbol, not the addition symbol, is traditionally used; they can also be subsets of rings, in which case the growth of <math>A+A</math> and <math>A</math>·<math>A</math> may be |

compared. | compared. | ||

===Computational number theory=== | ===Computational number theory=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Lehmer sieve.jpg|thumb|A Lehmer sieve, a primitive digital computer used to find primes and solve simple Diophantine equations.]] | |

| − | An early case is that of what we now call the | + | While the word ''algorithm'' goes back only to certain readers of al-Khwārizmī, careful descriptions of methods of solution are older than proofs: such methods (that is, algorithms) are as old as any recognisable mathematics—ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Vedic, Chinese—whereas proofs appeared only with the Greeks of the classical period. |

| − | or, what is the same, for finding the quantities whose existence is assured by the | + | An early case is that of what we now call the Euclidean algorithm. In its basic form (namely, as an algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor) it appears as Proposition 2 of Book VII in ''Elements'', together with a proof of correctness. However, in the form that is often used in number theory (namely, as an algorithm for finding integer solutions to an equation <math>a x + b y = c</math>, |

| + | or, what is the same, for finding the quantities whose existence is assured by the Chinese remainder theorem) it first appears in the works of Āryabhaṭa (5th–6th century CE) as an algorithm called | ||

''kuṭṭaka'' ("pulveriser"), without a proof of correctness. | ''kuṭṭaka'' ("pulveriser"), without a proof of correctness. | ||

| − | There are two main questions: "Can we compute this?" and "Can we compute it rapidly?" Anyone can test whether a number is prime or, if it is not, split it into prime factors; doing so rapidly is another matter. We now know fast algorithms for | + | There are two main questions: "Can we compute this?" and "Can we compute it rapidly?" Anyone can test whether a number is prime or, if it is not, split it into prime factors; doing so rapidly is another matter. We now know fast algorithms for testing primality, but, in spite of much work (both theoretical and practical), no truly fast algorithm for factoring. |

| − | The difficulty of a computation can be useful: modern protocols for | + | The difficulty of a computation can be useful: modern protocols for encrypting messages (for example, RSA) depend on functions that are known to all, but whose inverses are known only to a chosen few, and would take one too long a time to figure out on one's own. For example, these functions can be such that their inverses can be computed only if certain large integers are factorized. While many difficult computational problems outside number theory are known, most working encryption protocols nowadays are based on the difficulty of a few number-theoretical problems. |

| − | Some things may not be computable at all; in fact, this can be proven in some instances. For instance, in 1970, it was proven, as a solution to | + | Some things may not be computable at all; in fact, this can be proven in some instances. For instance, in 1970, it was proven, as a solution to Hilbert's 10th problem, that there is no Turing machine which can solve all Diophantine equations. In particular, this means that, given a computably enumerable set of axioms, there are Diophantine equations for which there is no proof, starting from the axioms, of whether the set of equations has or does not have integer solutions. (We would necessarily be speaking of Diophantine equations for which there are no integer solutions, since, given a Diophantine equation with at least one solution, the solution itself provides a proof of the fact that a solution exists. We cannot prove that a particular Diophantine equation is of this kind, since this would imply that it has no solutions.) |

| + | |||

| + | == Licensing == | ||

| + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Number_theory Number theory, Wikipedia] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 18:23, 5 January 2022

Number theory (or arithmetic or higher arithmetic in older usage) is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and integer-valued functions. German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) said, "Mathematics is the queen of the sciences—and number theory is the queen of mathematics." Number theorists study prime numbers as well as the properties of mathematical objects made out of integers (for example, rational numbers) or defined as generalizations of the integers (for example, algebraic integers).

Integers can be considered either in themselves or as solutions to equations (Diophantine geometry). Questions in number theory are often best understood through the study of analytical objects (for example, the Riemann zeta function) that encode properties of the integers, primes or other number-theoretic objects in some fashion (analytic number theory). One may also study real numbers in relation to rational numbers, for example, as approximated by the latter (Diophantine approximation).

The older term for number theory is arithmetic. By the early twentieth century, it had been superseded by "number theory". (The word "arithmetic" is used by the general public to mean "elementary calculations"; it has also acquired other meanings in mathematical logic, as in Peano arithmetic, and computer science, as in floating point arithmetic.) The use of the term arithmetic for number theory regained some ground in the second half of the 20th century, arguably in part due to French influence. In particular, arithmetical is commonly preferred as an adjective to number-theoretic.

Contents

History

Origins

Dawn of arithmetic

The earliest historical find of an arithmetical nature is a fragment of a table: the broken clay tablet Plimpton 322 (Larsa, Mesopotamia, ca. 1800 BCE) contains a list of "Pythagorean triples", that is, integers such that . The triples are too many and too large to have been obtained by brute force. The heading over the first column reads: "The takiltum of the diagonal which has been subtracted such that the width..."

The table's layout suggests that it was constructed by means of what amounts, in modern language, to the identity

which is implicit in routine Old Babylonian exercises. If some other method was used, the triples were first constructed and then reordered by , presumably for actual use as a "table", for example, with a view to applications.

It is not known what these applications may have been, or whether there could have been any; Babylonian astronomy, for example, truly came into its own only later. It has been suggested instead that the table was a source of numerical examples for school problems.

While Babylonian number theory—or what survives of Babylonian mathematics that can be called thus—consists of this single, striking fragment, Babylonian algebra (in the secondary-school sense of "algebra") was exceptionally well developed. Late Neoplatonic sources state that Pythagoras learned mathematics from the Babylonians. Much earlier sources state that Thales and Pythagoras traveled and studied in Egypt.

Euclid IX 21–34 is very probably Pythagorean; it is very simple material ("odd times even is even", "if an odd number measures [= divides] an even number, then it also measures [= divides] half of it"), but it is all that is needed to prove that is irrational. Pythagorean mystics gave great importance to the odd and the even. The discovery that is irrational is credited to the early Pythagoreans (pre-Theodorus). By revealing (in modern terms) that numbers could be irrational, this discovery seems to have provoked the first foundational crisis in mathematical history; its proof or its divulgation are sometimes credited to Hippasus, who was expelled or split from the Pythagorean sect. This forced a distinction between numbers (integers and the rationals—the subjects of arithmetic), on the one hand, and lengths and proportions (which we would identify with real numbers, whether rational or not), on the other hand.

The Pythagorean tradition spoke also of so-called polygonal or figurate numbers. While square numbers, cubic numbers, etc., are seen now as more natural than triangular numbers, pentagonal numbers, etc., the study of the sums of triangular and pentagonal numbers would prove fruitful in the early modern period (17th to early 19th century).

We know of no clearly arithmetical material in ancient Egyptian or Vedic sources, though there is some algebra in each. The Chinese remainder theorem appears as an exercise in Sunzi Suanjing (3rd, 4th or 5th century CE). (There is one important step glossed over in Sunzi's solution: it is the problem that was later solved by Āryabhaṭa's Kuṭṭaka – see below.)

There is also some numerical mysticism in Chinese mathematics, but, unlike that of the Pythagoreans, it seems to have led nowhere. Like the Pythagoreans' perfect numbers, magic squares have passed from superstition into recreation.

Classical Greece and the early Hellenistic period

Aside from a few fragments, the mathematics of Classical Greece is known to us either through the reports of contemporary non-mathematicians or through mathematical works from the early Hellenistic period. In the case of number theory, this means, by and large, Plato and Euclid, respectively.

While Asian mathematics influenced Greek and Hellenistic learning, it seems to be the case that Greek mathematics is also an indigenous tradition.

Eusebius, PE X, chapter 4 mentions of Pythagoras:

"In fact the said Pythagoras, while busily studying the wisdom of each nation, visited Babylon, and Egypt, and all Persia, being instructed by the Magi and the priests: and in addition to these he is related to have studied under the Brahmans (these are Indian philosophers); and from some he gathered astrology, from others geometry, and arithmetic and music from others, and different things from different nations, and only from the wise men of Greece did he get nothing, wedded as they were to a poverty and dearth of wisdom: so on the contrary he himself became the author of instruction to the Greeks in the learning which he had procured from abroad."

Aristotle claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans, and Cicero repeats this claim: Platonem ferunt didicisse Pythagorea omnia ("They say Plato learned all things Pythagorean").

Plato had a keen interest in mathematics, and distinguished clearly between arithmetic and calculation. (By arithmetic he meant, in part, theorising on number, rather than what arithmetic or number theory have come to mean.) It is through one of Plato's dialogues—namely, Theaetetus—that we know that Theodorus had proven that are irrational. Theaetetus was, like Plato, a disciple of Theodorus's; he worked on distinguishing different kinds of incommensurables, and was thus arguably a pioneer in the study of number systems. (Book X of Euclid's Elements is described by Pappus as being largely based on Theaetetus's work.)

Euclid devoted part of his Elements to prime numbers and divisibility, topics that belong unambiguously to number theory and are basic to it (Books VII to IX of Euclid's Elements). In particular, he gave an algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor of two numbers (the Euclidean algorithm; Elements, Prop. VII.2) and the first known proof of the infinitude of primes (Elements, Prop. IX.20).

In 1773, Lessing published an epigram he had found in a manuscript during his work as a librarian; it claimed to be a letter sent by Archimedes to Eratosthenes. The epigram proposed what has become known as Archimedes's cattle problem; its solution (absent from the manuscript) requires solving an indeterminate quadratic equation (which reduces to what would later be misnamed Pell's equation). As far as we know, such equations were first successfully treated by the Indian school. It is not known whether Archimedes himself had a method of solution.

Diophantus

Very little is known about Diophantus of Alexandria; he probably lived in the third century CE, that is, about five hundred years after Euclid. Six out of the thirteen books of Diophantus's Arithmetica survive in the original Greek and four more survive in an Arabic translation. The Arithmetica is a collection of worked-out problems where the task is invariably to find rational solutions to a system of polynomial equations, usually of the form or . Thus, nowadays, we speak of Diophantine equations when we speak of polynomial equations to which rational or integer solutions must be found.

One may say that Diophantus was studying rational points, that is, points whose coordinates are rational—on curves and algebraic varieties; however, unlike the Greeks of the Classical period, who did what we would now call basic algebra in geometrical terms, Diophantus did what we would now call basic algebraic geometry in purely algebraic terms. In modern language, what Diophantus did was to find rational parametrizations of varieties; that is, given an equation of the form (say) , his aim was to find (in essence) three rational functions such that, for all values of and , setting for gives a solution to

Diophantus also studied the equations of some non-rational curves, for which no rational parametrisation is possible. He managed to find some rational points on these curves (elliptic curves, as it happens, in what seems to be their first known occurrence) by means of what amounts to a tangent construction: translated into coordinate geometry (which did not exist in Diophantus's time), his method would be visualised as drawing a tangent to a curve at a known rational point, and then finding the other point of intersection of the tangent with the curve; that other point is a new rational point. (Diophantus also resorted to what could be called a special case of a secant construction.)

While Diophantus was concerned largely with rational solutions, he assumed some results on integer numbers, in particular that every integer is the sum of four squares (though he never stated as much explicitly).

Āryabhaṭa, Brahmagupta, Bhāskara

While Greek astronomy probably influenced Indian learning, to the point of introducing trigonometry, it seems to be the case that Indian mathematics is otherwise an indigenous tradition; in particular, there is no evidence that Euclid's Elements reached India before the 18th century.

Āryabhaṭa (476–550 CE) showed that pairs of simultaneous congruences , could be solved by a method he called kuṭṭaka, or pulveriser; this is a procedure close to (a generalisation of) the Euclidean algorithm, which was probably discovered independently in India. Āryabhaṭa seems to have had in mind applications to astronomical calculations.

Brahmagupta (628 CE) started the systematic study of indefinite quadratic equations—in particular, the misnamed Pell equation, in which Archimedes may have first been interested, and which did not start to be solved in the West until the time of Fermat and Euler. Later Sanskrit authors would follow, using Brahmagupta's technical terminology. A general procedure (the chakravala, or "cyclic method") for solving Pell's equation was finally found by Jayadeva (cited in the eleventh century; his work is otherwise lost); the earliest surviving exposition appears in Bhāskara II's Bīja-gaṇita (twelfth century).

Indian mathematics remained largely unknown in Europe until the late eighteenth century; Brahmagupta and Bhāskara's work was translated into English in 1817 by Henry Colebrooke.

Arithmetic in the Islamic golden age

In the early ninth century, the caliph Al-Ma'mun ordered translations of many Greek mathematical works and at least one Sanskrit work (the Sindhind, which may be Brahmagupta's Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta). Diophantus's main work, the Arithmetica, was translated into Arabic by Qusta ibn Luqa (820–912). Part of the treatise al-Fakhri (by al-Karajī, 953 – ca. 1029) builds on it to some extent. According to Rashed Roshdi, Al-Karajī's contemporary Ibn al-Haytham knew what would later be called Wilson's theorem.

Western Europe in the Middle Ages

Other than a treatise on squares in arithmetic progression by Fibonacci—who traveled and studied in north Africa and Constantinople—no number theory to speak of was done in western Europe during the Middle Ages. Matters started to change in Europe in the late Renaissance, thanks to a renewed study of the works of Greek antiquity. A catalyst was the textual emendation and translation into Latin of Diophantus' Arithmetica.

Early modern number theory

Fermat

Pierre de Fermat (1607–1665) never published his writings; in particular, his work on number theory is contained almost entirely in letters to mathematicians and in private marginal notes. In his notes and letters, he scarcely wrote any proofs - he had no models in the area.

Over his lifetime, Fermat made the following contributions to the field:

- One of Fermat's first interests was perfect numbers (which appear in Euclid, Elements IX) and amicable numbers; these topics led him to work on integer divisors, which were from the beginning among the subjects of the correspondence (1636 onwards) that put him in touch with the mathematical community of the day.

- In 1638, Fermat claimed, without proof, that all whole numbers can be expressed as the sum of four squares or fewer.

- Fermat's little theorem (1640): if a is not divisible by a prime p, then

- If a and b are coprime, then is not divisible by any prime congruent to −1 modulo 4; and every prime congruent to 1 modulo 4 can be written in the form . These two statements also date from 1640; in 1659, Fermat stated to Huygens that he had proven the latter statement by the method of infinite descent.

- In 1657, Fermat posed the problem of solving as a challenge to English mathematicians. The problem was solved in a few months by Wallis and Brouncker. Fermat considered their solution valid, but pointed out they had provided an algorithm without a proof (as had Jayadeva and Bhaskara, though Fermat wasn't aware of this). He stated that a proof could be found by infinite descent.

- Fermat stated and proved (by infinite descent) in the appendix to Observations on Diophantus (Obs. XLV) that has no non-trivial solutions in the integers. Fermat also mentioned to his correspondents that has no non-trivial solutions, and that this could also be proven by infinite descent. The first known proof is due to Euler (1753; indeed by infinite descent).

- Fermat claimed (Fermat's Last Theorem) to have shown there are no solutions to for all ; this claim appears in his annotations in the margins of his copy of Diophantus.

Euler

The interest of Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) in number theory was first spurred in 1729, when a friend of his, the amateur Goldbach, pointed him towards some of Fermat's work on the subject. This has been called the "rebirth" of modern number theory, after Fermat's relative lack of success in getting his contemporaries' attention for the subject. Euler's work on number theory includes the following:

- Proofs for Fermat's statements. This includes Fermat's little theorem (generalised by Euler to non-prime moduli); the fact that if and only if ; initial work towards a proof that every integer is the sum of four squares (the first complete proof is by Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1770), soon improved by Euler himself); the lack of non-zero integer solutions to (implying the case n=4 of Fermat's last theorem, the case n=3 of which Euler also proved by a related method).

- Pell's equation, first misnamed by Euler. He wrote on the link between continued fractions and Pell's equation.

- First steps towards analytic number theory. In his work of sums of four squares, partitions, pentagonal numbers, and the distribution of prime numbers, Euler pioneered the use of what can be seen as analysis (in particular, infinite series) in number theory. Since he lived before the development of complex analysis, most of his work is restricted to the formal manipulation of power series. He did, however, do some very notable (though not fully rigorous) early work on what would later be called the Riemann zeta function.

- Quadratic forms. Following Fermat's lead, Euler did further research on the question of which primes can be expressed in the form , some of it prefiguring quadratic reciprocity.

- Diophantine equations. Euler worked on some Diophantine equations of genus 0 and 1. In particular, he studied Diophantus's work; he tried to systematise it, but the time was not yet ripe for such an endeavour—algebraic geometry was still in its infancy. He did notice there was a connection between Diophantine problems and elliptic integrals, whose study he had himself initiated.

Lagrange, Legendre, and Gauss

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) was the first to give full proofs of some of Fermat's and Euler's work and observations—for instance, the four-square theorem and the basic theory of the misnamed "Pell's equation" (for which an algorithmic solution was found by Fermat and his contemporaries, and also by Jayadeva and Bhaskara II before them.) He also studied quadratic forms in full generality (as opposed to )—defining their equivalence relation, showing how to put them in reduced form, etc.

Adrien-Marie Legendre (1752–1833) was the first to state the law of quadratic reciprocity. He also conjectured what amounts to the prime number theorem and Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions. He gave a full treatment of the equation and worked on quadratic forms along the lines later developed fully by Gauss. In his old age, he was the first to prove Fermat's Last Theorem for (completing work by Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, and crediting both him and Sophie Germain).

In his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (1798), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) proved the law of quadratic reciprocity and developed the theory of quadratic forms (in particular, defining their composition). He also introduced some basic notation (congruences) and devoted a section to computational matters, including primality tests. The last section of the Disquisitiones established a link between roots of unity and number theory:

The theory of the division of the circle...which is treated in sec. 7 does not belong by itself to arithmetic, but its principles can only be drawn from higher arithmetic.

In this way, Gauss arguably made a first foray towards both Évariste Galois's work and algebraic number theory.

Maturity and division into subfields

Starting early in the nineteenth century, the following developments gradually took place:

- The rise to self-consciousness of number theory (or higher arithmetic) as a field of study.

- The development of much of modern mathematics necessary for basic modern number theory: complex analysis, group theory, Galois theory—accompanied by greater rigor in analysis and abstraction in algebra.

- The rough subdivision of number theory into its modern subfields—in particular, analytic and algebraic number theory.

Algebraic number theory may be said to start with the study of reciprocity and cyclotomy, but truly came into its own with the development of abstract algebra and early ideal theory and valuation theory; see below. A conventional starting point for analytic number theory is Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions (1837), whose proof introduced L-functions and involved some asymptotic analysis and a limiting process on a real variable. The first use of analytic ideas in number theory actually goes back to Euler (1730s), who used formal power series and non-rigorous (or implicit) limiting arguments. The use of complex analysis in number theory comes later: the work of Bernhard Riemann (1859) on the zeta function is the canonical starting point; Jacobi's four-square theorem (1839), which predates it, belongs to an initially different strand that has by now taken a leading role in analytic number theory (modular forms).

The history of each subfield is briefly addressed in its own section below; see the main article of each subfield for fuller treatments. Many of the most interesting questions in each area remain open and are being actively worked on.

Main subdivisions

Elementary number theory

The term elementary generally denotes a method that does not use complex analysis. For example, the prime number theorem was first proven using complex analysis in 1896, but an elementary proof was found only in 1949 by Erdős and Selberg. The term is somewhat ambiguous: for example, proofs based on complex Tauberian theorems (for example, Wiener–Ikehara) are often seen as quite enlightening but not elementary, in spite of using Fourier analysis, rather than complex analysis as such. Here as elsewhere, an elementary proof may be longer and more difficult for most readers than a non-elementary one.

Number theory has the reputation of being a field many of whose results can be stated to the layperson. At the same time, the proofs of these results are not particularly accessible, in part because the range of tools they use is, if anything, unusually broad within mathematics.

Analytic number theory

Analytic number theory may be defined

- in terms of its tools, as the study of the integers by means of tools from real and complex analysis; or

- in terms of its concerns, as the study within number theory of estimates on size and density, as opposed to identities.

Some subjects generally considered to be part of analytic number theory, for example, sieve theory, are better covered by the second rather than the first definition: some of sieve theory, for instance, uses little analysis, yet it does belong to analytic number theory.

The following are examples of problems in analytic number theory: the prime number theorem, the Goldbach conjecture (or the twin prime conjecture, or the Hardy–Littlewood conjectures), the Waring problem and the Riemann hypothesis. Some of the most important tools of analytic number theory are the circle method, sieve methods and L-functions (or, rather, the study of their properties). The theory of modular forms (and, more generally, automorphic forms) also occupies an increasingly central place in the toolbox of analytic number theory.

One may ask analytic questions about algebraic numbers, and use analytic means to answer such questions; it is thus that algebraic and analytic number theory intersect. For example, one may define prime ideals (generalizations of prime numbers in the field of algebraic numbers) and ask how many prime ideals there are up to a certain size. This question can be answered by means of an examination of Dedekind zeta functions, which are generalizations of the Riemann zeta function, a key analytic object at the roots of the subject.[81] This is an example of a general procedure in analytic number theory: deriving information about the distribution of a sequence (here, prime ideals or prime numbers) from the analytic behavior of an appropriately constructed complex-valued function.

Algebraic number theory

An algebraic number is any complex number that is a solution to some polynomial equation with rational coefficients; for example, every solution of (say) is an algebraic number. Fields of algebraic numbers are also called algebraic number fields, or shortly number fields. Algebraic number theory studies algebraic number fields. Thus, analytic and algebraic number theory can and do overlap: the former is defined by its methods, the latter by its objects of study.

It could be argued that the simplest kind of number fields (viz., quadratic fields) were already studied by Gauss, as the discussion of quadratic forms in Disquisitiones arithmeticae can be restated in terms of ideals and norms in quadratic fields. (A quadratic field consists of all numbers of the form , where and are rational numbers and is a fixed rational number whose square root is not rational.) For that matter, the 11th-century chakravala method amounts—in modern terms—to an algorithm for finding the units of a real quadratic number field. However, neither Bhāskara nor Gauss knew of number fields as such.

The grounds of the subject as we know it were set in the late nineteenth century, when ideal numbers, the theory of ideals and valuation theory were developed; these are three complementary ways of dealing with the lack of unique factorisation in algebraic number fields. (For example, in the field generated by the rationals and , the number can be factorised both as and ; all of , , and are irreducible, and thus, in a naïve sense, analogous to primes among the integers.) The initial impetus for the development of ideal numbers (by Kummer) seems to have come from the study of higher reciprocity laws, that is, generalisations of quadratic reciprocity.

Number fields are often studied as extensions of smaller number fields: a field L is said to be an extension of a field K if L contains K. (For example, the complex numbers C are an extension of the reals R, and the reals R are an extension of the rationals Q.) Classifying the possible extensions of a given number field is a difficult and partially open problem. Abelian extensions—that is, extensions L of K such that the Galois group Gal(L/K) of L over K is an abelian group—are relatively well understood. Their classification was the object of the programme of class field theory, which was initiated in the late 19th century (partly by Kronecker and Eisenstein) and carried out largely in 1900–1950.