Difference between revisions of "Real Numbers:Absolute Value"

(Created page with "== Absolute Values == ''Absolute Values'' represented using two vertical bars, <math>\vert</math>, are common in Algebra. They are meant to signify the number's distance from...") |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

\end{cases}</math>. | \end{cases}</math>. | ||

Because it can only be the case that <math>y=-x\text{ if }x<0</math> and <math>y=x\text{ if }x\ge0</math>, it is not possible for <math>|x|<0</math>. However, since <math>x</math> has no restriction, the domain, <math>A</math>, has no restriction. Thus, if <math>B</math> represents the range of the function, then <math>A=\{x\in\mathbb{R}\}</math> and <math>B=\{y\ge0 | y\in\mathbb{R}\}</math>. | Because it can only be the case that <math>y=-x\text{ if }x<0</math> and <math>y=x\text{ if }x\ge0</math>, it is not possible for <math>|x|<0</math>. However, since <math>x</math> has no restriction, the domain, <math>A</math>, has no restriction. Thus, if <math>B</math> represents the range of the function, then <math>A=\{x\in\mathbb{R}\}</math> and <math>B=\{y\ge0 | y\in\mathbb{R}\}</math>. | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| − | + | '''Definition: Domain and Range''' | |

| + | : Let <math>f(x)=|x|</math> whose mapping is <math>f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}</math> represent the absolute value function. If <math>A</math> is the domain and <math>B</math> is the range, then <math>A=\{x\in\mathbb{R}\}</math> and <math>B=\{y\ge0 | y\in\mathbb{R}\}</math>. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

By the above definition, there exists an ''absolute minimum'' to the parent function, and it exists at the origin, <math>O(0,0)</math> | By the above definition, there exists an ''absolute minimum'' to the parent function, and it exists at the origin, <math>O(0,0)</math> | ||

| Line 39: | Line 41: | ||

:If <math>x\in A</math> and <math>f(-x)=f(x)</math>, then <math>f</math> is even. | :If <math>x\in A</math> and <math>f(-x)=f(x)</math>, then <math>f</math> is even. | ||

:If <math>x\in A</math> and <math>f(-x)=-f(x)</math>, then <math>f</math> is odd. | :If <math>x\in A</math> and <math>f(-x)=-f(x)</math>, then <math>f</math> is odd. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Proof: <math>f(x)=|x|</math> is even | ||

Let <math>f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}:x\mapsto |x|</math>. By definition, | Let <math>f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}:x\mapsto |x|</math>. By definition, | ||

:<math>f(x)=|x|=\begin{cases} | :<math>f(x)=|x|=\begin{cases} | ||

| Line 49: | Line 52: | ||

:<math>f(-x)=-(-x)=x</math> | :<math>f(-x)=-(-x)=x</math> | ||

:<math>\Rightarrow f(-x)=f(x)\blacksquare</math> | :<math>\Rightarrow f(-x)=f(x)\blacksquare</math> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | Because <math>f(x)</math> is even, it is also the case that it is ''symmetrical'' | + | Because <math>f(x)</math> is even, it is also the case that it is ''symmetrical''. |

==== One-to-one and onto? ==== | ==== One-to-one and onto? ==== | ||

| Line 56: | Line 59: | ||

:If <math>u,v\in A</math>, and <math>f(u)=f(v)\Rightarrow u=v</math>, then <math>f(x)</math> is injective. | :If <math>u,v\in A</math>, and <math>f(u)=f(v)\Rightarrow u=v</math>, then <math>f(x)</math> is injective. | ||

:If for all <math>b\in B</math> there is an <math>a\in A</math> such that <math>f(a)=b</math>, then <math>f(x)</math> is surjective. | :If for all <math>b\in B</math> there is an <math>a\in A</math> such that <math>f(a)=b</math>, then <math>f(x)</math> is surjective. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Proof: <math>f(x)=|x|</math> is non-injective | ||

Suppose <math>u,v\in\mathbb{R}</math> and <math>f(u)=f(v)</math>. By the previous proof, we showed <math>f(x)</math> is even. As such, we can use the value <math>v=-u</math> to make the following statement: | Suppose <math>u,v\in\mathbb{R}</math> and <math>f(u)=f(v)</math>. By the previous proof, we showed <math>f(x)</math> is even. As such, we can use the value <math>v=-u</math> to make the following statement: | ||

:<math>f(u)=f(v)\Rightarrow u\ne v</math> | :<math>f(u)=f(v)\Rightarrow u\ne v</math> | ||

Therefore, <math>f(x)</math> is non-injective. | Therefore, <math>f(x)</math> is non-injective. | ||

| − | + | ||

Because we have not established how to prove these statements through algebraic manipulation, we will be deriving properties as we go to gain a further understanding of these new functions. Establishing whether a function is surjective is simply through checking the definition (negating if otherwise to establish it as non-surjective). | Because we have not established how to prove these statements through algebraic manipulation, we will be deriving properties as we go to gain a further understanding of these new functions. Establishing whether a function is surjective is simply through checking the definition (negating if otherwise to establish it as non-surjective). | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | Suppose <math>b\in\mathbb{R}</math>. There exists an element <math>b=-1\in\mathbb{R}</math>, for which <math>f(x)=|x|\ne -1</math> for all <math>x\in\mathbb{R}</math>. | + | Proof: <math>f(x)=|x|</math> is non-surjective |

| − | + | Suppose <math>b\in\mathbb{R}</math>. There exists an element <math>b=-1\in\mathbb{R}</math>, for which <math>f(x)=|x|\ne -1</math> for all <math>x\in\mathbb{R}</math>. | |

| − | + | ||

==== Intercepts and Inflections of the Parent Function ==== | ==== Intercepts and Inflections of the Parent Function ==== | ||

| Line 84: | Line 88: | ||

Many times, one will not be working with the parent function. Many real life applications of this function involve at least some manipulation to either the input or the output: vertical stretching/contraction, horizontal stretching/contraction, reflection about the <math>x</math>-axis, reflection about the <math>y</math>-axis, and vertical/horizontal shifting. Luckily, not much changes when it comes to the manipulation of these functions. The exceptions will be talked about in more detail: | Many times, one will not be working with the parent function. Many real life applications of this function involve at least some manipulation to either the input or the output: vertical stretching/contraction, horizontal stretching/contraction, reflection about the <math>x</math>-axis, reflection about the <math>y</math>-axis, and vertical/horizontal shifting. Luckily, not much changes when it comes to the manipulation of these functions. The exceptions will be talked about in more detail: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| − | + | '''Vertical Expansion/Contraction/Flipping''' | |

| + | Let <math>f(x)=|x|</math> and <math>g(x)=A\cdot f(x)</math>. There must be an <math>\left(x_{0},y_{0}\right)\in f(x)\Leftrightarrow \left(x_{0},Ay_{0}\right)\in g(x)</math>. Thus, | ||

* If <math>A>1</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is an expansion of <math>f(x)</math> by a factor of <math>A</math>. | * If <math>A>1</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is an expansion of <math>f(x)</math> by a factor of <math>A</math>. | ||

* If <math>0<A<1</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a contraction of <math>f(x)</math> by a factor of <math>A</math>. | * If <math>0<A<1</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a contraction of <math>f(x)</math> by a factor of <math>A</math>. | ||

| − | * If <math>A<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a reflection of <math>f(x)</math> about the <math>x</math>-axis. | + | * If <math>A<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a reflection of <math>f(x)</math> about the <math>x</math>-axis.</blockquote> |

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| − | + | '''Vertical Shift''' | |

| + | Let <math>f(x)=|x|</math> and <math>g(x)=f(x)+b</math>. There must be an <math>\left(x_{0},y_{0}\right)\in f(x)\Leftrightarrow \left(x_{0},y_{0}-b\right)\in g(x)</math>. Thus, | ||

* If <math>b>0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is an upward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>b</math>. | * If <math>b>0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is an upward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>b</math>. | ||

| − | * If <math>b<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a downward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>b</math>. | + | * If <math>b<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a downward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>b</math>.</blockquote> |

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| + | '''Horizontal Shift''' | ||

text=Let <math>f(x)=|x|</math> and <math>g(x)=f(x+a)</math>. There must be an <math>\left(x_{0},y_{0}\right)\in f(x)\Leftrightarrow \left(x_{0}-a, y_{0}\right)\in g(x)</math>. Thus, | text=Let <math>f(x)=|x|</math> and <math>g(x)=f(x+a)</math>. There must be an <math>\left(x_{0},y_{0}\right)\in f(x)\Leftrightarrow \left(x_{0}-a, y_{0}\right)\in g(x)</math>. Thus, | ||

* If <math>a>0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a leftward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>a</math>. | * If <math>a>0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a leftward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>a</math>. | ||

| − | * If <math>a<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a rightward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>a</math>. | + | * If <math>a<0</math>, then <math>g(x)</math> is a rightward shift of <math>f(x)</math> by <math>a</math>.</blockquote> |

| − | The properties not listed above are exceptions to the general rule about functions found in the chapter | + | The properties not listed above are exceptions to the general rule about functions found in the chapter. The exceptions are not anything substantial. The only difference with what we found generally versus what we have provided above are simply a result of what we found in the previous section. |

* There is no reflection about the <math>y</math>-axis because the function is even and symmetrical. | * There is no reflection about the <math>y</math>-axis because the function is even and symmetrical. | ||

* There is no horizontal expansion and contraction because it gives the same result as vertical expansion and contraction (this will be proven later). | * There is no horizontal expansion and contraction because it gives the same result as vertical expansion and contraction (this will be proven later). | ||

| Line 108: | Line 115: | ||

This subsection is absolutely not optional. You will be asked these questions very explicitly, so it is a good idea to understand this section. If you didn't read the previous subsection, you are not going to understand how any of this makes sense. | This subsection is absolutely not optional. You will be asked these questions very explicitly, so it is a good idea to understand this section. If you didn't read the previous subsection, you are not going to understand how any of this makes sense. | ||

| − | Fortunately, the idea behind graphing any arbitrary function is mostly dependent on what you know about the function. Therefore, we can easily be able to graph functions | + | Fortunately, the idea behind graphing any arbitrary function is mostly dependent on what you know about the function. Therefore, we can easily be able to graph functions. |

| − | + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | |

| − | |||

| − | :'''Method 1''': Follow procedure from Algebra of Functions | + | '''Example 1.2(a)''': Graph the following absolute value function: |

| + | <center><math>f(x)=\frac{1}{2}|2x+6|-5</math></center></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Method 1''': Follow procedure from Algebra of Functions | ||

This method will work for any arbitrary function. However, it will not always be the quickest method for absolute value functions. We follow the following steps. Let <math>f(x)</math> be the parent function and <math>g(x)=Af(ax+b)+c</math>. | This method will work for any arbitrary function. However, it will not always be the quickest method for absolute value functions. We follow the following steps. Let <math>f(x)</math> be the parent function and <math>g(x)=Af(ax+b)+c</math>. | ||

| Line 124: | Line 133: | ||

Since <math>f(x)=\frac{1}{2}|2x+6|-5</math> has <math>A=\frac{1}{2}</math>, <math>a=2</math>, <math>b=6</math>, and <math>c=-5</math>, we may apply these steps as given to get to our desired result. As this should be review, we will not be meticulously graphing each step. As such, only the final function (and the parent function in red) will be shown. | Since <math>f(x)=\frac{1}{2}|2x+6|-5</math> has <math>A=\frac{1}{2}</math>, <math>a=2</math>, <math>b=6</math>, and <math>c=-5</math>, we may apply these steps as given to get to our desired result. As this should be review, we will not be meticulously graphing each step. As such, only the final function (and the parent function in red) will be shown. | ||

| − | + | '''Method 2''': Find absolute minimum or maximum, graph one half, reflect. | |

| − | While '''method 1''' will always work for any arbitrary, continuous function, '''method | + | While '''method 1''' will always work for any arbitrary, continuous function, '''method 2''' is fastest for the absolute value function that composes a linear function. |

First, we should try to find the vertex. We know from Algebra of Functions that the only thing that will affect the location of the vertex in even functions is the <math>x-a</math> term on the inner composed linear function and the vertical shift of the entire function, <math>c</math>. | First, we should try to find the vertex. We know from Algebra of Functions that the only thing that will affect the location of the vertex in even functions is the <math>x-a</math> term on the inner composed linear function and the vertical shift of the entire function, <math>c</math>. | ||

| Line 149: | Line 158: | ||

''To be continued.'' | ''To be continued.'' | ||

| − | {{ | + | == Absolute Value Equations == |

| + | |||

| + | Now, let's say that we're given the equation <math>\left\vert k\right\vert=8</math> and we are asked to solve for <math>k</math>. What number would satisfy the equation of <math>\left\vert k\right\vert=8</math>? 8 would work, but -8 would also work. That's why there can be two solutions to one equation. How come this is true? That is what the next example is for. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Example 2.0(a)''': Formally define the function below:<center><math>f(k)=|2k+6|</math></center> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | Recall what the absolute value represents: it is the distance of that number to the left or right of the starting point, the point where the inner function is zero. Recall the formal definition of the absolute value function: | ||

| + | :<math>f(x)=|x|=\begin{cases} | ||

| + | -x\text{ if }x<0\\ | ||

| + | x\text{ if }x\ge0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | We want to formally define the function <math>f(k)=|2k+6|</math>. Let <math>x=k</math> First, we need to find where <math>2k+6=0</math>. | ||

| + | :<math>2k+6=0</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\Leftrightarrow 2k=-6</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\Leftrightarrow k=-3</math> | ||

| + | From that, it is safe to say that the following is true: | ||

| + | :<math>f(k)=|2k+6|=\begin{cases} | ||

| + | -(2k+6)\text{ if }k<-3\\ | ||

| + | 2k+6\text{ if }k\ge3 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is important to know how to do this so that we may formally apply an algorithm throughout this entire chapter. For now, we will be exploring ways to solve these functions based on the examples given, including the formalizing of an algorithm, which we will give later. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | '''Example 2.0(b)''': Solve for <math>k</math>:<center><math>|2k+6|=8</math></center> </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since we formally defined the function in '''Example 0''', we will write the definition down. | ||

| + | : <math>f(k)=|2k+6|=\begin{cases} | ||

| + | -(2k+6)\text{ if }k<-3\\ | ||

| + | 2k+6\text{ if }k\ge-3 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | [[File:Absolute Value Equation Graphed.svg|frame]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is important to realize what the equation is saying: "there is a function <math>y=f(k)</math> equal to <math>y=8</math> such that <math>\exists k\in\mathbb{R}</math>." As defined in the opening section, the following function is non-injective and non-surjective. Therefore, there must be a <math>k_{1}\text{ and }k_{2}</math> such that it satisfies <math>f(k)=8</math>. Therefore, the following must be true | ||

| + | <center><math>2k + 6 = 8\quad\text{AND}\quad -(2k + 6) = 8</math>.</center> | ||

| + | All that is left to do is to solve the two equations for <math>k</math> for each given case, which will be differentiated by its positive and negative case: | ||

| + | :Negative case | ||

| + | ::<math>-(2k+6)=8</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Leftrightarrow 2k+6=-8</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Leftrightarrow 2k=-14</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Leftrightarrow k=-7</math> | ||

| + | :Positive case | ||

| + | ::<math>2k+6=8</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Leftrightarrow 2k=2</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Leftrightarrow k=1</math> | ||

| + | We found our two solutions for <math>k</math>: | ||

| + | <center><math>k=-7,1\blacksquare</math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above example demonstrates an algorithm that is commonly taught in high schools and many universities since it applicable to every absolute value equation. The steps for the algorithm will now be stated. Given <math>|g(x)|+c=f(x)</math>: | ||

| + | # Isolate the absolute value function so that is equal to another function, or <math>|g(x)|=f(x)-c</math>. | ||

| + | # Write the equation so that you solve for the composed function into two such cases. Given <math>|g(x)|=f(x)-c</math>, | ||

| + | ::* Solve for <math>g(x)=f(x)-c</math> and | ||

| + | ::* Solve for <math>g(x)=-(f(x)-c)</math>. | ||

| + | A basic principle of solving these absolute value equations is the need to keep the absolute value by itself. This should be enough for most people to understand, yet this phrasing can be a little ambiguous to some students. As such, a lot of practice problems may be in order here. We will be applying all the steps to algorithm outlined above instead of going through the process of formally solving these equations because '''Example 1''' was meant to show that the algorithm is true. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Example 2.0(c)''': Solve for <math>k</math>:<center><math>3|2k + 6| = 12</math></center> </blockquote> | ||

| + | We will show you two ways to solve this equation. The first is the standard way, the second will show you something not usually taught. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Standard way: Multiply the constant multiple by its inverse.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We'd have to divide both sides by <math>3</math> to get the absolute value by itself. We would set up the two different equations using similar reasoning as in the first example: | ||

| + | <center><math>2k + 6 = 4\quad\text{OR}\quad2k + 6 = -4</math>.</center> | ||

| + | Then, we'd solve, by subtracting the 6 from both sides and dividing both sides by 2 to get the <math>k</math> by itself, resulting in <math>k = -5, -1</math>. We will leave the solving part as an exercise to the reader. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Other way: "Distribute" the three into the absolute value.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Play close attention to the steps and reasoning laid out herein, for the reasoning for why this works is just as important as the person using the trick, if not moreso. Let us first generalize the problem. Let there be a positive, non-zero constant multiple <math>c</math> multiplied to the absolute value equation <math>|2k+6|</math>: | ||

| + | <center><math>c\cdot|2k+6|=|c|\cdot|2k+6|\quad\text{OR}\quad c\cdot|2k + 6|=|-c|\cdot|2k+6|</math>.</center> | ||

| + | Let us assume both are true. If both statements are true, then you are allowed to distribute the positive constant <math>c</math> inside the absolute value. Otherwise, this method is invalid! | ||

| + | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

| + | |c|\cdot|2k+6|&=|c(2k+6)|&\qquad|-c|\cdot|2k+6|&=|-c(2k+6)|\\ | ||

| + | &=|2ck+6c|&\qquad &=|-2ck-6c|=|-(2ck+6c)|\\ | ||

| + | &=|1|\cdot|2ck+6c|={\color{red}1\cdot|2ck+6c|}&\qquad &=|-1|\cdot|2ck+6c|={\color{red}1\cdot|2ck+6c|} | ||

| + | \end{align}</math> | ||

| + | Notice the two equations have the same highlighted answer in red, meaning so long as the value of the constant multiple <math>c</math> is positive, you are allowed to distribute the <math>c</math> inside the absolute value bars. However, this "distributive property" needed the property that multiplying two absolute values is the same as the absolute value of the product. We need to prove this is true first before one can use this in their proof. For the student that spotted this mistake, you may have a good logical mind on one's shoulder, or a good eye for detail. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''<u>Proof:</u>'''<center><math>|b|\cdot|c|=|bc|</math></center> | ||

| + | Let us start with what we know: | ||

| + | *<math>|x|= | ||

| + | \begin{cases} | ||

| + | x, & \text{if} & x\ge0 \\ | ||

| + | -x, & \text{if} & x<0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | :* If <math>a<0</math>, then <math>|a|=-a\ge0</math>. Else, if <math>a\ge0</math>, then <math>|a|\ge0</math>. | ||

| + | Let <math>b,c\in\mathbb{R}</math>, <math>|b|=B</math>, <math>|c|=C</math>, and <math>b\cdot c=m</math>. The following three cases apply: | ||

| + | *<math>bc=m<0\Rightarrow |m|=-m>0</math>. This simply means that for some product <math>bc</math> that equals a negative number <math>m</math>, the absolute value of that is <math>-m</math>, or the distance from zero. Because <math>m<0</math>, multiplying the two sides by <math>-1</math> will change the less than to a greater than, or <math>m<0\Leftrightarrow -m>0</math>. | ||

| + | *<math>bc=m=0\Rightarrow |m|=m=0</math>. For some product <math>bc</math> that equals a number <math>m=0</math>, the absolute value of that is <math>0</math>. | ||

| + | *<math>bc=m>0\Rightarrow |m|=m>0</math>. For some product <math>bc</math> that equals a positive number <math>m</math>, the absolute value of the product is <math>m</math>. | ||

| + | Given <math>|bc|=|m|</math> always result in some positive number (and zero), we can conclude that the function is equivalent to the following: | ||

| + | :<math>|b\cdot c| = |m| = \begin{cases} | ||

| + | m, & \text{if }m\ge0\\ | ||

| + | -m, & \text{if }m<0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | Let <math>|b|\cdot |c| = B\cdot C = n</math>. Since <math>|b|=B>0</math> and <math>|c|=C>0</math>, <math>B\cdot C=n>0</math>. This means that <math>n=|n|</math>. Therefore, <math>|b|\cdot |c| = |n|</math>. This allows us to conclude that | ||

| + | :<math>|b|\cdot |c| = n = |n| = \begin{cases} | ||

| + | n, & \text{if }n\ge0\\ | ||

| + | -n, & \text{if }n<0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | <math>|bc|=|m|</math> implies that <math>bc\ge 0\vee bc<0</math>. However, <math>|b|\cdot |c| = n</math> where <math>n=|n|</math>. We have shown that <math>\forall b,c\in\mathbb{R}</math>, we will always see that <math>|bc|>0</math> and <math>|b|\cdot |c|>0</math>. Further, we already know that <math>|x|>0</math>, meaning even if <math>x<0</math>, <math>|x|>0</math>. Thus, <math>|m|=n=|n|</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, <math>\forall b,c\in\mathbb{R}</math>, <math>|b|\cdot|c|=|bc|\blacksquare</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One nice thing about this proof is how we can use this to conclude that any function multiplied by another function will result in multiplying the inner functions within the absolute values. All we have to do is assume that is equals some other function instead of another number, as implicitly written within this proof. The only necessary change one needs to make is simply define all the variables within as functions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By confirming the general case, we may be employ this trick when we see it again. Let us apply this property to the original problem (this gives us the green result below): | ||

| + | :<math>3|2k+6|={\color{green}|6k+18|=12}</math> | ||

| + | This all implies that | ||

| + | <center><math>6k+18=12\quad\text{OR}\quad 6k+18=-12</math>.</center> | ||

| + | From there, a simple use of algebra will show that the answer to the original problem is again <math>k = -5, -1</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let us change the previous problem a little so that the constant multiple is now negative. Without changing much else, what will be true as a result? Let us find out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | '''Example 2.0(d)''': Solve for <math>k</math>:<center><math>-4|2k + 6| = 8</math></center> </blockquote> | ||

| + | We will attempt to the problem in two different ways: the standard way and the other way, which we will explain later. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Standard way: Multiply the constant multiple by its inverse.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Divide like the previous problem, so the equation would look like this: <math>|2k + 6| = -2</math>. Recall what the absolute value represents: it is the <u>distance</u> of that number to the left or right of the starting point, zero. With this, do you notice anything strange? When you evaluate an absolute value, you will <u>always</u> get a positive number because the distance must always be positive. Because this is means a logically impossible situation, there are '''no <u>real</u> solutions'''. Notice how we specifically mentioned "real" solutions. This is because we are certain that the solutions in the real set, <math>\mathbb{R}</math>, do not exist. However, there might be some set out there which would have solutions for this type of equation. Because of this posibility, we need to be mathematically rigorous and specifically state "no real solutions." | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Other way: "Distribute" the constant multiple into the absolute value.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Here, we notice that the constant multiple <math>c<0</math>. The problem with that is there is no <math>g</math> such that <math>|g|<0</math>. The only way this would be true is for <math>-|g|<0</math> because | ||

| + | :<math>-|g|<0\qquad\text{Divide both sides by }-1</math> | ||

| + | :<math>|g|>0</math> | ||

| + | With this property, we may therefore only distribute the constant multiple as <math>|c|</math> with a negative <math>-1</math> as a factor outside the absolute value. As such, | ||

| + | :<math>-4|2k+6|=-|8k+24|=8\qquad\text{Divide both sides by }-1</math> | ||

| + | :<math>|8k+24|=-8</math> | ||

| + | It seems the other way has us multiply a constant by its inverse to both sides. Either way, this "other method" still gave us the same answer: there is '''no real solution'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The problem this time will be a little different. Keep in mind the principle we had in mind throughout all the examples so far, and be careful because a trap is set in this problem. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> </blockquote> | ||

| + | '''Example 2.0(e)''': Solve for <math>x</math>:<center><math>|3x-3|-3=2x-10</math></center> </blockquote> | ||

| + | There are many we ways can attempt to find solutions to this problem. We will do this the standard and allow any student to do it however they so desire. | ||

| + | :<math>|3x-3|-3=2x-10\qquad\text{Add the }3\text{ to both sides.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>|3x-3|=2x-7</math> | ||

| + | Because the absolute value is isolated, we can begin with our generalized procedure. Assuming <math>2x-7>0</math>, we may begin by denoting these two equations: | ||

| + | * <math>3x-3=2x-7</math> | ||

| + | * <math>3x-3=-(2x-7)</math> | ||

| + | These are only true if <math>2x-7>0</math>. For now, <u>assume</u> this condition is true. Let us solve for <math>x</math> with each respective equation: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Equation <math>3x-3=2x-7</math> | ||

| + | :<math>3x-3=2x-7\qquad\text{Add }3\text{ and subtract }2x\text{ on both sides.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>x=-4</math> | ||

| + | Equation <math>3x-3=-(2x-7)</math> | ||

| + | :<math>3x-3=-(2x-7)\qquad\text{Distribute }-1\text{.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>3x-3=-2x+7\qquad\quad\text{Add }3\text{ and add }2x\text{ on both sides.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>5x=10\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\text{Divide }5\text{ on both sides.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>x=2</math> | ||

| + | We have two <u>potential</u> solutions to the equation. Try to answer why we said potential here based on what you know so far about this problem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why did we state we had two <u>potential</u> solutions? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because we had to <u>assume</u> that <math>2x-7>0</math> and <math>|3x-3|=2x-7</math> is true for the provided <math>x</math>. | ||

| + | Because of this, we have to verify the solutions to this equation exist. Therefore, let us substitute those values into the equation: | ||

| + | :<math>|3(-4)-3|=2(-4)-7</math>. Notice that the right-hand side is negative. Also, the left-hand side and the right-hand side are not equivalent. Therefore, this is not a solution. | ||

| + | :<math>|3(2)-3|=2(2)-7</math>. Notice the right-hand side is negative, again. Also, the left-hand side and the right-hand side are not equivalent. Therefore, this cannot be a solution. | ||

| + | This equations has '''no real solutions'''. More specifically, it has '''two extraneous solutions''' (i.e. the solutions we found do not satisfy the equality property when we substitute them back in). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite doing the procedure outlined since the first problem, you obtain two extraneous solutions. This is not the fault of the procedure but a simple result of the equation itself. Because the left-hand side must always be positive, it means the right-hand side must be positive as well. Along with that restriction is the fact that the two sides may not equal the other for the values whereby only positive values are given. This is all a matter of properties of functions. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | '''Example 2.0(f)''': Solve for <math>a</math>:<center><math>6\left\vert5\frac{a}{6}+\frac{1}{12}\right\vert=\frac{3}{5}|15a+15|</math></center> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | All the properties learned will be needed here, so let us hope you did not skip anything here. It will certainly make our lives easier if we know the properties we are about to employ in this problem. | ||

| + | :<math>6\left\vert5\frac{a}{6}+\frac{1}{12}\right\vert=\frac{3}{5}|15a+15|\qquad\text{Distribute, so to speak, the constant terms.}</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\left\vert5a+\frac{1}{2}\right\vert=|9a+9|</math> | ||

| + | Looking at the second equation might be the first declaration of absurdity. However, an application of the fundamental properties of absolute values is enough to do this problem. | ||

| + | : <math>5a+\frac{1}{2}=|9a+9|</math> | ||

| + | : <math>5a+\frac{1}{2}=-|9a+9|</math> | ||

| + | Peel the problem one layer at a time. For this one, we will categorize equations based on where they come from; this should hopefully explain the dashes: 3-1 is first equation formulated from <math>5a+\frac{1}{2}=|9a+9|</math>, for example. | ||

| + | : <math>9a+9=5a+\frac{1}{2}</math>|3-1|center | ||

| + | : <math>9a+9=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> | ||

| + | : <math>-(9a+9)=5a+\frac{1}{2}</math> | ||

| + | : <math>-(9a+9)=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> | ||

| + | We can demonstrate that some equations are equivalents of the other. For example, <math>9a+9=5a+\frac{1}{2}</math> and <math>-(9a+9)=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> are equivalent, since dividing both sides of <math>-(9a+9)=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> by <math>-1</math> gives <math>9a+9=5a+\frac{1}{2}</math>. Further, <math>9a+9=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> and <math>-(9a+9)=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> are equivalent (multiply both sides of equation <math>-(9a+9)=-\left(5a+\frac{1}{2}\right)</math> by <math>-1</math>). After determining all the equations that are equivalent, distribute <math>-1</math> to the corresponding parentheses. | ||

| + | : <math>9a+9=5a+\frac{1}{2}</math> | ||

| + | : <math>9a+9=-5a-\frac{1}{2}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now all that is left to do is solve the equations. We will leave this step as an exercise for the reader. There are two potential solutions: <math>a=-\frac{19}{28},-\frac{17}{8}</math>. All that is left to do is verify that the equation in the question is true when looking at these specific values of <math>a</math>: | ||

| + | :<math>a=-\frac{19}{28}</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\left\vert5\left(-\frac{19}{28}\right)+\frac{1}{2}\right\vert=\left\vert9\left(-\frac{19}{28}\right)+9\right\vert</math> is true. The two sides give the same value: <math>\frac{81}{8}=10.125</math>. | ||

| + | :<math>a=-\frac{17}{8}</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\left\vert5\left(-\frac{17}{8}\right)+\frac{1}{2}\right\vert=\left\vert9\left(-\frac{17}{8}\right)+9\right\vert</math> is true. The two sides give the same value: <math>\frac{81}{28}\approx2.893</math>. | ||

| + | Because both solutions are true, the two solutions are <math>a=-\frac{19}{28},-\frac{17}{8}\blacksquare</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Inequalities with Absolute Values == | ||

| + | It is important to keep in mind that any function can be less than any other function. For example, <math>2x-5<54-13x</math> has any solutions for <math>x<\frac{59}{13}=3+\frac{14}{15}</math>. So long as the value for <math>x</math> is within that range, the function <math>2x-5</math> is less than the output of <math>54-13x</math>. The algebra for inequalities of <math>f(x)=|x|</math> requires a bit more of demonstration to understand. While the methods we use will not be proven, per se, our examples and explanations should give a good intuition behind the idea of find the inequalities of absolute values. | ||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | '''Example 3.0(a)''': <math>|10-20x|<50</math> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | First, let us simplify the following expression through the method we demonstrated in the previous section (factoring the inside of the absolute value and bringing the constant out). Keep in mind, since we are switching the sides for which we view the equation, 50 is the left instead of right, we must also "flip" the inequality to be consistent with the original equation. | ||

| + | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

| + | 50&>|10-20x|\\ | ||

| + | &>|10\cdot(1-2x)|\\ | ||

| + | &>10\cdot|1-2x| | ||

| + | \end{align}</math> | ||

| + | From there, it should be easy to see that | ||

| + | :<math>|1-2x|<5</math> | ||

| + | Let us further analyze this situation. What the above equation is saying is <math>y=|1-2x|</math> is less than the function <math>y=5</math>. We want to make sure the inside value is less than five. Because the absolute value describes the distance, there are two realities to the function. Let <math>A(x)=|1-2x|</math> | ||

| + | :<math>A(x)=|x|= | ||

| + | \begin{cases} | ||

| + | 1-2x, & \text{if}& x\ge\frac{1}{2} \\ | ||

| + | -(1-2x), & \text{if}& x<\frac{1}{2} | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | Because there are two "pieces" to the function <math>A(x)</math>, and we want each piece to be less than 5, | ||

| + | :<math>1-2x<5</math> and <math>-(1-2x)<5</math> | ||

| + | We will demonstrate the more common procedure in the next example. For now, this intuition should begin to form an idea of algebraic analysis. We will solve the left-hand then the right-hand case. | ||

| + | :Solving for <math>x</math> in <math>|1-2x|<5</math>. | ||

| + | :: ''Left-hand case'': | ||

| + | ::: <math>1-2x<5</math> | ||

| + | ::: Recall how multiplying both sides by a negative factor requires us to "flip" the inequality. Therefore, solving for <math>x</math>: | ||

| + | ::: <math>\Leftrightarrow x>-2</math> | ||

| + | :: ''Right-hand case'': | ||

| + | ::: <math>-(1-2x)<5</math> | ||

| + | ::: <math>\Leftrightarrow 1-2x>-5</math> | ||

| + | ::: <math>\Leftrightarrow x<3</math> | ||

| + | We have found a possible distribution of values that allows the following equation to be true, where <math>|2x-5|<5</math>, and it is for values of <math>x</math> in between <math>-2</math> and <math>3</math>, non-inclusive. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above example is an intuition behind how solving for inequalities work. Technically speaking, we could make a proof for why we have to "operate" (take the steps seen above) absolute value inequalities this way. However, this will be a little too technical and involve a lot of generalization that could potentially confuse students rather than enlighten. If the student feels the challenge is worth, then one may try the proof of the steps we derived below. This is considered standard procedure (according to many High School textbooks). | ||

| + | # Simplify until only the "absolute value bar term" is left. | ||

| + | # Solve by taking the inside and relating it by the inequality for the "left-hand" values; taking the same expression found inside the absolute value, for the "right-hand" equation, negate the related term and flip the inequality to then solve. | ||

| + | # Rewrite <math>x</math> into necessary notatioon. | ||

| + | Although the procedure may seem to be confusing, we are really only trying to make the algorithm as specific as possible. In reality, we will show just how easy it is to apply this algorithm for the problem above. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background: white; border: 1px solid black; padding: 1em;"> | ||

| + | '''Example 3.0(a) (REPEAT)''': <math>|10-20x|<50</math> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | Let us skip to the most simplified form. | ||

| + | :<math>|1-2x|<5</math> | ||

| + | Now let us apply the above algorithm. | ||

| + | :<math>1-2x<5</math> and <math>1-2x>-5</math> (notice the negation and flipping for the right hand equation). | ||

| + | From there, we will solve. | ||

| + | :Solving for <math>x</math> in <math>|1-2x|<5</math>. | ||

| + | :: ''Left-hand case'': | ||

| + | ::: <math>1-2x<5</math> | ||

| + | ::: Recall how multiplying both sides by a negative factor requires us to "flip" the inequality. Therefore, solving for <math>x</math>: | ||

| + | ::: <math>\Leftrightarrow x>-2</math> | ||

| + | :: ''Right-hand case'': | ||

| + | ::: <math>1-2x>-5</math> | ||

| + | ::: <math>\Leftrightarrow x<3</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are two possible reasons why this procedure exists. For one, it allows us to quickly solve for <math>x</math> in the "right-hand" equation without the need for double the amount of multiplications necessary to solve for <math>x</math> (it lessens the amount of times we have to flip the inequality). Next, it allows us to focus more on the idea behind absolute value equations (the value inside will be positive, and hence, we want to find all values that allow us to find all possible solutions). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nevertheless, keep in mind how we found this procedure, and it was through applying the function definition of absolute values. In reality, we did the exact same thing for absolute value ''equations''. The only difference in application of algorithm applies to the inequality, which further "complicates" matters by introducing a new concept to the non-injective absolute value function. Through finding two solutions, we gave two possible ranges for values of <math>x</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hopefully, this example should further shine a light into what many high schoolers think to be "black magic" among finding solutions to absolute value inequalities and equalities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Licensing== | ||

| + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/CLEP_College_Algebra/Absolute_Value_Equations Absolute Value Equations, Wikibooks: CLEP College Algebra] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 7 November 2021

Contents

Absolute Values

Absolute Values represented using two vertical bars, , are common in Algebra. They are meant to signify the number's distance from 0 on a number line. If the number is negative, it becomes positive. And if the number was positive, it remains positive:

For a formal definition:

This can be read aloud as the following:

If , then

The formal definition is simply a declaration of what the function represents at certain restrictions of the -value. For any , the output of the graph of the function on the plane is that of the linear function . If , then the output is that of the linear function .

For our purposes, it does not technically matter whether or . As long as you pick one and are consistent with it, it does not matter how this is defined. By convention, it is usually defined as in the beginning formal definition.

Please note that the opposite (the negative, -) of a negative number is a positive. For example, the opposite of is . Usually, some books and teachers would refer to opposite number as the negative of the given magnitude. For convenience, this may be used, so always keep in mind this shortcut in language.

Properties of the Absolute Value Function

We will define the properties of the absolute value function. This will be important to know when taking the CLEP exam since it can drastically speed up the process of solving absolute value equations. Finally, the practice problems in this section will test you on your knowledge on absolute value equations. We recommend you learn these concepts to the best of your abilities. However, this will not be explicitly necessary by the time one takes the exam.

Domain and Range

Let whose mapping is . By definition,

- .

Because it can only be the case that and , it is not possible for . However, since has no restriction, the domain, , has no restriction. Thus, if represents the range of the function, then and .

Definition: Domain and Range

- Let whose mapping is represent the absolute value function. If is the domain and is the range, then and .

By the above definition, there exists an absolute minimum to the parent function, and it exists at the origin,

Even or odd?

Recall the definition of an even and an odd function. Let there be a function

- If and , then is even.

- If and , then is odd.

Proof: is even Let . By definition,

- .

Suppose . Let .

Because is even, it is also the case that it is symmetrical.

One-to-one and onto?

Recall the definitions of injective and surjective.

- If , and , then is injective.

- If for all there is an such that , then is surjective.

Proof: is non-injective Suppose and . By the previous proof, we showed is even. As such, we can use the value to make the following statement:

Therefore, is non-injective.

Because we have not established how to prove these statements through algebraic manipulation, we will be deriving properties as we go to gain a further understanding of these new functions. Establishing whether a function is surjective is simply through checking the definition (negating if otherwise to establish it as non-surjective).

Proof: is non-surjective Suppose . There exists an element , for which for all .

Intercepts and Inflections of the Parent Function

With all the information provided from the previous sections, we can derive the graph of the parent function . It is even, and therefore, symmetrical about the -axis since there is an -intercept at . Finally, because we know the domain and range, we know the minimum of the function is at , and we know the definition of the function, we can easily show that the graph of is the following image to the right (Figure 1).

A summary of what you should see from the graph is this:

- Domain: .

- Range: .

- There is an absolute minimum at .

- There is one -intercept at .

- There is one -intercept at .

- The graph is even and symmetrical about the -axis.

- The graph is non-injective and non-surjective.

- The graph has no inflection point.

Transformations of the Parent Function

Many times, one will not be working with the parent function. Many real life applications of this function involve at least some manipulation to either the input or the output: vertical stretching/contraction, horizontal stretching/contraction, reflection about the -axis, reflection about the -axis, and vertical/horizontal shifting. Luckily, not much changes when it comes to the manipulation of these functions. The exceptions will be talked about in more detail:

Vertical Expansion/Contraction/Flipping Let and . There must be an . Thus,

- If , then is an expansion of by a factor of .

- If , then is a contraction of by a factor of .

- If , then is a reflection of about the -axis.

Vertical Shift Let and . There must be an . Thus,

- If , then is an upward shift of by .

- If , then is a downward shift of by .

Horizontal Shift text=Let and . There must be an . Thus,

- If , then is a leftward shift of by .

- If , then is a rightward shift of by .

The properties not listed above are exceptions to the general rule about functions found in the chapter. The exceptions are not anything substantial. The only difference with what we found generally versus what we have provided above are simply a result of what we found in the previous section.

- There is no reflection about the -axis because the function is even and symmetrical.

- There is no horizontal expansion and contraction because it gives the same result as vertical expansion and contraction (this will be proven later).

We now have all the information we will need to know about absolute value functions now.

Graphing Absolute Value Functions

This subsection is absolutely not optional. You will be asked these questions very explicitly, so it is a good idea to understand this section. If you didn't read the previous subsection, you are not going to understand how any of this makes sense.

Fortunately, the idea behind graphing any arbitrary function is mostly dependent on what you know about the function. Therefore, we can easily be able to graph functions.

Example 1.2(a): Graph the following absolute value function:

Method 1: Follow procedure from Algebra of Functions

This method will work for any arbitrary function. However, it will not always be the quickest method for absolute value functions. We follow the following steps. Let be the parent function and .

- Factor so that .

- Horizontally shift to the left/right by .

- Horizontally contract/expand by .

- Vertically expand/contract/flip by .

- Vertically shift upward/downward by .

Since has , , , and , we may apply these steps as given to get to our desired result. As this should be review, we will not be meticulously graphing each step. As such, only the final function (and the parent function in red) will be shown.

Method 2: Find absolute minimum or maximum, graph one half, reflect.

While method 1 will always work for any arbitrary, continuous function, method 2 is fastest for the absolute value function that composes a linear function.

First, we should try to find the vertex. We know from Algebra of Functions that the only thing that will affect the location of the vertex in even functions is the term on the inner composed linear function and the vertical shift of the entire function, .

Rewriting the absolute value equation as shown below will allow us to find the vertex of the function.

This then tells us the vertex is at .

This method then tells us to graph the slopes. However, how should that work? Recall the formal definition of an arbitrary absolute value function:

In the above definition of a general absolute value function, . This means that where the -value implies a vertex on the function, that is how we restrict absolute value function.

In our instance, , for which , so . We can say, thusly, that

- :

To be continued.

Absolute Value Equations

Now, let's say that we're given the equation and we are asked to solve for . What number would satisfy the equation of ? 8 would work, but -8 would also work. That's why there can be two solutions to one equation. How come this is true? That is what the next example is for.

Example 2.0(a): Formally define the function below:

Recall what the absolute value represents: it is the distance of that number to the left or right of the starting point, the point where the inner function is zero. Recall the formal definition of the absolute value function:

We want to formally define the function . Let First, we need to find where .

From that, it is safe to say that the following is true:

It is important to know how to do this so that we may formally apply an algorithm throughout this entire chapter. For now, we will be exploring ways to solve these functions based on the examples given, including the formalizing of an algorithm, which we will give later.

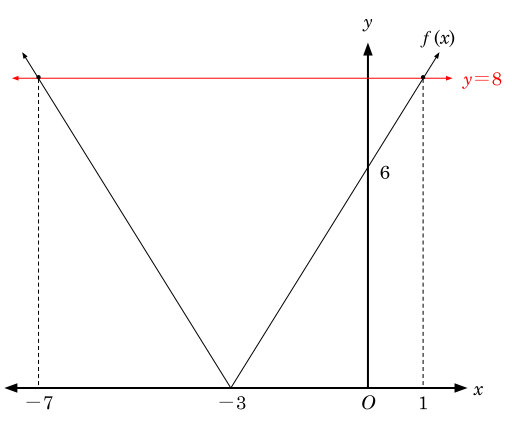

Example 2.0(b): Solve for :

Since we formally defined the function in Example 0, we will write the definition down.

It is important to realize what the equation is saying: "there is a function equal to such that ." As defined in the opening section, the following function is non-injective and non-surjective. Therefore, there must be a such that it satisfies . Therefore, the following must be true

All that is left to do is to solve the two equations for for each given case, which will be differentiated by its positive and negative case:

- Negative case

- Positive case

We found our two solutions for :

The above example demonstrates an algorithm that is commonly taught in high schools and many universities since it applicable to every absolute value equation. The steps for the algorithm will now be stated. Given :

- Isolate the absolute value function so that is equal to another function, or .

- Write the equation so that you solve for the composed function into two such cases. Given ,

- Solve for and

- Solve for .

A basic principle of solving these absolute value equations is the need to keep the absolute value by itself. This should be enough for most people to understand, yet this phrasing can be a little ambiguous to some students. As such, a lot of practice problems may be in order here. We will be applying all the steps to algorithm outlined above instead of going through the process of formally solving these equations because Example 1 was meant to show that the algorithm is true.

Example 2.0(c): Solve for :

We will show you two ways to solve this equation. The first is the standard way, the second will show you something not usually taught.

Standard way: Multiply the constant multiple by its inverse.

We'd have to divide both sides by to get the absolute value by itself. We would set up the two different equations using similar reasoning as in the first example:

Then, we'd solve, by subtracting the 6 from both sides and dividing both sides by 2 to get the by itself, resulting in . We will leave the solving part as an exercise to the reader.

Other way: "Distribute" the three into the absolute value.

Play close attention to the steps and reasoning laid out herein, for the reasoning for why this works is just as important as the person using the trick, if not moreso. Let us first generalize the problem. Let there be a positive, non-zero constant multiple multiplied to the absolute value equation :

Let us assume both are true. If both statements are true, then you are allowed to distribute the positive constant inside the absolute value. Otherwise, this method is invalid!

Notice the two equations have the same highlighted answer in red, meaning so long as the value of the constant multiple is positive, you are allowed to distribute the inside the absolute value bars. However, this "distributive property" needed the property that multiplying two absolute values is the same as the absolute value of the product. We need to prove this is true first before one can use this in their proof. For the student that spotted this mistake, you may have a good logical mind on one's shoulder, or a good eye for detail.

Proof:

Let us start with what we know:

- If , then . Else, if , then .

Let , , , and . The following three cases apply:

- . This simply means that for some product that equals a negative number , the absolute value of that is , or the distance from zero. Because , multiplying the two sides by will change the less than to a greater than, or .

- . For some product that equals a number , the absolute value of that is .

- . For some product that equals a positive number , the absolute value of the product is .

Given always result in some positive number (and zero), we can conclude that the function is equivalent to the following:

Let . Since and , . This means that . Therefore, . This allows us to conclude that

implies that . However, where . We have shown that , we will always see that and . Further, we already know that , meaning even if , . Thus, .

Therefore, , .

One nice thing about this proof is how we can use this to conclude that any function multiplied by another function will result in multiplying the inner functions within the absolute values. All we have to do is assume that is equals some other function instead of another number, as implicitly written within this proof. The only necessary change one needs to make is simply define all the variables within as functions.

By confirming the general case, we may be employ this trick when we see it again. Let us apply this property to the original problem (this gives us the green result below):

This all implies that

From there, a simple use of algebra will show that the answer to the original problem is again .

Let us change the previous problem a little so that the constant multiple is now negative. Without changing much else, what will be true as a result? Let us find out.

Example 2.0(d): Solve for :

We will attempt to the problem in two different ways: the standard way and the other way, which we will explain later.

Standard way: Multiply the constant multiple by its inverse.

Divide like the previous problem, so the equation would look like this: . Recall what the absolute value represents: it is the distance of that number to the left or right of the starting point, zero. With this, do you notice anything strange? When you evaluate an absolute value, you will always get a positive number because the distance must always be positive. Because this is means a logically impossible situation, there are no real solutions. Notice how we specifically mentioned "real" solutions. This is because we are certain that the solutions in the real set, , do not exist. However, there might be some set out there which would have solutions for this type of equation. Because of this posibility, we need to be mathematically rigorous and specifically state "no real solutions."

Other way: "Distribute" the constant multiple into the absolute value.

Here, we notice that the constant multiple . The problem with that is there is no such that . The only way this would be true is for because

With this property, we may therefore only distribute the constant multiple as with a negative as a factor outside the absolute value. As such,

It seems the other way has us multiply a constant by its inverse to both sides. Either way, this "other method" still gave us the same answer: there is no real solution.

The problem this time will be a little different. Keep in mind the principle we had in mind throughout all the examples so far, and be careful because a trap is set in this problem.

Example 2.0(e): Solve for :

There are many we ways can attempt to find solutions to this problem. We will do this the standard and allow any student to do it however they so desire.

Because the absolute value is isolated, we can begin with our generalized procedure. Assuming , we may begin by denoting these two equations:

These are only true if . For now, assume this condition is true. Let us solve for with each respective equation:

Equation

Equation

We have two potential solutions to the equation. Try to answer why we said potential here based on what you know so far about this problem.

Why did we state we had two potential solutions?

Because we had to assume that and is true for the provided . Because of this, we have to verify the solutions to this equation exist. Therefore, let us substitute those values into the equation:

- . Notice that the right-hand side is negative. Also, the left-hand side and the right-hand side are not equivalent. Therefore, this is not a solution.

- . Notice the right-hand side is negative, again. Also, the left-hand side and the right-hand side are not equivalent. Therefore, this cannot be a solution.

This equations has no real solutions. More specifically, it has two extraneous solutions (i.e. the solutions we found do not satisfy the equality property when we substitute them back in).

Despite doing the procedure outlined since the first problem, you obtain two extraneous solutions. This is not the fault of the procedure but a simple result of the equation itself. Because the left-hand side must always be positive, it means the right-hand side must be positive as well. Along with that restriction is the fact that the two sides may not equal the other for the values whereby only positive values are given. This is all a matter of properties of functions.

Example 2.0(f): Solve for :

All the properties learned will be needed here, so let us hope you did not skip anything here. It will certainly make our lives easier if we know the properties we are about to employ in this problem.

Looking at the second equation might be the first declaration of absurdity. However, an application of the fundamental properties of absolute values is enough to do this problem.

Peel the problem one layer at a time. For this one, we will categorize equations based on where they come from; this should hopefully explain the dashes: 3-1 is first equation formulated from , for example.

- |3-1|center

We can demonstrate that some equations are equivalents of the other. For example, and are equivalent, since dividing both sides of by gives . Further, and are equivalent (multiply both sides of equation by ). After determining all the equations that are equivalent, distribute to the corresponding parentheses.

Now all that is left to do is solve the equations. We will leave this step as an exercise for the reader. There are two potential solutions: . All that is left to do is verify that the equation in the question is true when looking at these specific values of :

-

- is true. The two sides give the same value: .

-

- is true. The two sides give the same value: .

Because both solutions are true, the two solutions are .

Inequalities with Absolute Values

It is important to keep in mind that any function can be less than any other function. For example, has any solutions for . So long as the value for is within that range, the function is less than the output of . The algebra for inequalities of requires a bit more of demonstration to understand. While the methods we use will not be proven, per se, our examples and explanations should give a good intuition behind the idea of find the inequalities of absolute values.

Example 3.0(a):

First, let us simplify the following expression through the method we demonstrated in the previous section (factoring the inside of the absolute value and bringing the constant out). Keep in mind, since we are switching the sides for which we view the equation, 50 is the left instead of right, we must also "flip" the inequality to be consistent with the original equation.

From there, it should be easy to see that

Let us further analyze this situation. What the above equation is saying is is less than the function . We want to make sure the inside value is less than five. Because the absolute value describes the distance, there are two realities to the function. Let

Because there are two "pieces" to the function , and we want each piece to be less than 5,

- and

We will demonstrate the more common procedure in the next example. For now, this intuition should begin to form an idea of algebraic analysis. We will solve the left-hand then the right-hand case.

- Solving for in .

- Left-hand case:

- Recall how multiplying both sides by a negative factor requires us to "flip" the inequality. Therefore, solving for :

- Right-hand case:

- Left-hand case:

We have found a possible distribution of values that allows the following equation to be true, where , and it is for values of in between and , non-inclusive.

The above example is an intuition behind how solving for inequalities work. Technically speaking, we could make a proof for why we have to "operate" (take the steps seen above) absolute value inequalities this way. However, this will be a little too technical and involve a lot of generalization that could potentially confuse students rather than enlighten. If the student feels the challenge is worth, then one may try the proof of the steps we derived below. This is considered standard procedure (according to many High School textbooks).

- Simplify until only the "absolute value bar term" is left.

- Solve by taking the inside and relating it by the inequality for the "left-hand" values; taking the same expression found inside the absolute value, for the "right-hand" equation, negate the related term and flip the inequality to then solve.

- Rewrite into necessary notatioon.

Although the procedure may seem to be confusing, we are really only trying to make the algorithm as specific as possible. In reality, we will show just how easy it is to apply this algorithm for the problem above.

Example 3.0(a) (REPEAT):

Let us skip to the most simplified form.

Now let us apply the above algorithm.

- and (notice the negation and flipping for the right hand equation).

From there, we will solve.

- Solving for in .

- Left-hand case:

- Recall how multiplying both sides by a negative factor requires us to "flip" the inequality. Therefore, solving for :

- Right-hand case:

- Left-hand case:

There are two possible reasons why this procedure exists. For one, it allows us to quickly solve for in the "right-hand" equation without the need for double the amount of multiplications necessary to solve for (it lessens the amount of times we have to flip the inequality). Next, it allows us to focus more on the idea behind absolute value equations (the value inside will be positive, and hence, we want to find all values that allow us to find all possible solutions).

Nevertheless, keep in mind how we found this procedure, and it was through applying the function definition of absolute values. In reality, we did the exact same thing for absolute value equations. The only difference in application of algorithm applies to the inequality, which further "complicates" matters by introducing a new concept to the non-injective absolute value function. Through finding two solutions, we gave two possible ranges for values of .

Hopefully, this example should further shine a light into what many high schoolers think to be "black magic" among finding solutions to absolute value inequalities and equalities.

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- Absolute Value Equations, Wikibooks: CLEP College Algebra under a CC BY-SA license