Difference between revisions of "Polar Equations and Graphs"

Rylee.taylor (talk | contribs) (fixing link to go straight to pdf) |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Polar graph paper.svg|thumb|right|300px|A polar grid with several angles labeled in degrees]] | ||

| + | The '''polar coordinate system''' is a two-dimensional coordinate system in which each point on a plane is determined by an angle and a distance. The polar coordinate system is especially useful in situations where the relationship between two points is most easily expressed in terms of angles and distance; in the more familiar Cartesian coordinate system or rectangular coordinate system, such a relationship can only be found through trigonometric formulae. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As the coordinate system is two-dimensional, each point is determined by two polar coordinates: the radial coordinate and the angular coordinate. The radial coordinate (usually denoted as <math>r</math>) denotes the point's distance from a central point known as the ''pole'' (equivalent to the ''origin'' in the Cartesian system). The angular coordinate (also known as the polar angle or the azimuth angle, and usually denoted by <math>\theta</math> or <math>t</math>) denotes the positive or anticlockwise (counterclockwise) angle required to reach the point from the 0° ray or ''polar axis'' (which is equivalent to the positive <math>x</math>-axis in the Cartesian coordinate plane). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Plotting points with polar coordinates== | ||

| + | [[Image:CircularCoordinates.png|thumb|250px|The points (3,60°) and (4,210°) on a polar coordinate system]] | ||

| + | Each point in the polar coordinate system can be described with the two polar coordinates, which are usually called <math>r</math> (the radial coordinate) and θ (the angular coordinate, polar angle, or azimuth angle, sometimes represented as <math>\phi</math> or <math>t</math>). The <math>r</math> coordinate represents the radial distance from the pole, and the θ coordinate represents the anticlockwise (counterclockwise) angle from the <math>0^\circ</math> ray (sometimes called the polar axis), known as the positive <math>x</math>-axis on the Cartesian coordinate plane. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, the polar coordinates <math>(3,60^\circ)</math> would be plotted as a point 3 units from the pole on the <math>60^\circ</math> ray. The coordinates <math>(-3,240^\circ)</math> would also be plotted at this point because a negative radial distance is measured as a positive distance on the opposite ray (the ray reflected about the origin, which differs from the original ray by <math>180^\circ</math>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | One important aspect of the polar coordinate system, not present in the Cartesian coordinate system, is that a single point can be expressed with an infinite number of different coordinates. This is because any number of multiple revolutions can be made around the central pole without affecting the actual location of the point plotted. In general, the point <math>(r,\theta)</math> can be represented as <math>(r,\theta\pm360^\circ k)</math> or <math>(-r,\theta\pm(2k+1)180^\circ)</math> , where <math>k</math> is any integer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The arbitrary coordinates <math>(0,\theta)</math> are conventionally used to represent the pole, as regardless of the θ coordinate, a point with radius 0 will always be on the pole. To get a unique representation of a point, it is usual to limit <math>r</math> to negative and non-negative numbers <math>r\ge0</math> and <math>\theta</math> to the interval <math>[0,360^\circ)</math> or <math>(-180^\circ,180^\circ]</math> (or, in radian measure, <math>[0,2\pi)</math> or <math>(-\pi,\pi]</math>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Angles in polar notation are generally expressed in either degrees or radians, using the conversion <math>2\pi\ \text{rad}=360^\circ</math> . The choice depends largely on the context. Navigation applications use degree measure, while some physics applications (specifically rotational mechanics) and almost all mathematical literature on calculus use radian measure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Converting between polar and Cartesian coordinates=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Polar to cartesian.svg|right|thumb|250px|A diagram illustrating the conversion formulae]] | ||

| + | The two polar coordinates <math>r,\theta</math> can be converted to the Cartesian coordinates <math>x,y</math> by using the trigonometric functions sine and cosine: | ||

| + | :<math>x=r\cos(\theta)</math> | ||

| + | :<math>y=r\sin(\theta)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | while the two Cartesian coordinates <math>x,y</math> can be converted to polar coordinate <math>r</math> by | ||

| + | :<math>r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}</math> (by a simple application of the Pythagorean theorem). | ||

| + | |||

| + | To determine the angular coordinate <math>\theta</math> , the following two ideas must be considered: | ||

| + | *For <math>r=0</math> , <math>\theta</math> can be set to any real value. | ||

| + | *For <math>r\ne0</math> , to get a unique representation for <math>\theta</math> , it must be limited to an interval of size <math>2\pi</math> . Conventional choices for such an interval are <math>[0,2\pi)</math> and <math>(-\pi,\pi]</math> . | ||

| + | |||

| + | To obtain <math>\theta</math> in the interval <math>[0,2\pi)</math> , the following may be used (<math>\arctan</math> denotes the inverse of the tangent function): | ||

| + | :<math>\theta= | ||

| + | \begin{cases} | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)&\text{if }x>0\text{ and }y\ge0\\ | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+2\pi&\text{if }x>0\text{ and }y<0\\ | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+\pi&\text{if }x<0\\ | ||

| + | \frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y>0\\ | ||

| + | \frac{3\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y<0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To obtain <math>\theta</math> in the interval <math>(-\pi,\pi]</math> , the following may be used: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>\theta= | ||

| + | \begin{cases} | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)&\text{if }x>0\\ | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+\pi&\text{if }x<0\text{ and }y\ge0\\ | ||

| + | \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)-\pi&\text{if }x<0\text{ and }y<0\\ | ||

| + | \frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y>0\\ | ||

| + | -\frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y<0 | ||

| + | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | One may avoid having to keep track of the numerator and denominator signs by use of the atan2 function, which has separate arguments for the numerator and the denominator. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Polar equations== | ||

| + | The equation defining an algebraic curve expressed in polar coordinates is known as a ''polar equation''. In many cases, such an equation can simply be specified by defining <math>r</math> as a function of <math>\theta</math> . The resulting curve then consists of points of the form <math>\big(r(\theta),\theta\big)</math> and can be regarded as the graph of the polar function <math>r</math> . | ||

| + | |||

| + | Different forms of symmetry can be deduced from the equation of a polar function <math>r</math> . If <math>r(-\theta)=r(\theta)</math> the curve will be symmetrical about the horizontal <math>(0^\circ/180^\circ)</math> ray, if <math>r(\pi-\theta)=r(\theta)</math> it will be symmetric about the vertical <math>(90^\circ/270^\circ)</math> ray, and if <math>r(\theta-\alpha^\circ)=r(\theta)</math> it will be rotationally symmetric <math>\alpha^\circ</math> counterclockwise about the pole. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because of the circular nature of the polar coordinate system, many curves can be described by a rather simple polar equation, whereas their Cartesian form is much more intricate. Among the best known of these curves are the polar rose, Archimedean spiral, lemniscate, limaçon, and cardioid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the circle, line, and polar rose below, it is understood that there are no restrictions on the domain and range of the curve. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Circle=== | ||

| + | [[Image:circle_r=1.PNG|thumb|right|A circle with equation <math>r(\theta)=1</math>]] | ||

| + | The general equation for a circle with a center at <math>(r_0,\phi)</math> and radius <math>a</math> is | ||

| + | :<math>r^2-2rr_0\cos(\theta-\varphi)+r_0^2=a^2</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This can be simplified in various ways, to conform to more specific cases, such as the equation | ||

| + | :<math>r(\theta)=a</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | for a circle with a center at the pole and radius <math>a</math> . | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Line=== | ||

| + | ''Radial'' lines (those running through the pole) are represented by the equation | ||

| + | :<math>\theta=\varphi</math> | ||

| + | where <math>\phi</math> is the angle of elevation of the line; that is, <math>\phi=\arctan(m)</math> where <math>m</math> is the slope of the line in the Cartesian coordinate system. The non-radial line that crosses the radial line <math>\theta=\phi</math> perpendicularly at the point <math>(r_0,\phi)</math> has the equation | ||

| + | :<math>r(\theta)=r_0\sec(\theta-\varphi)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Polar rose=== | ||

| + | [[Image:rose_r=2sin(4theta).PNG|thumb|right|A polar rose with equation <math>r(\theta)=2\sin(4\theta)</math>]] | ||

| + | A polar rose is a famous mathematical curve that looks like a petaled flower, and that can be expressed as a simple polar equation, | ||

| + | :<math>r(\theta)=a\cos(k\theta+\phi_0)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | for any constant <math>\phi_0</math> (including 0). If <math>k</math> is an integer, these equations will produce a <math>k</math>-petaled rose if <math>k</math> is odd, or a <math>2k</math>-petaled rose if <math>k</math> is even. If <math>k</math> is rational but not an integer, a rose-like shape may form but with overlapping petals. Note that these equations never define a rose with 2, 6, 10, 14, etc. petals. The variable <math>a</math> represents the length of the petals of the rose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Archimedean spiral=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Archimedian_spiral.PNG|thumb|right|One arm of an Archimedean spiral with equation <math>r(\theta)=\theta</math> for <math>\theta\in(0,6\pi)</math>]] | ||

| + | The Archimedean spiral is a famous spiral that was discovered by Archimedes, which also can be expressed as a simple polar equation. It is represented by the equation | ||

| + | :<math>r(\theta)=a+b\theta</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Changing the parameter <math>a</math> will turn the spiral, while <math>b</math> controls the distance between the arms, which for a given spiral is always constant. The Archimedean spiral has two arms, one for <math>\theta>0</math> and one for <math>\theta<0</math> . The two arms are smoothly connected at the pole. Taking the mirror image of one arm across the <math>90^\circ/270^\circ</math> line will yield the other arm. This curve is notable as one of the first curves, after the Conic Sections, to be described in a mathematical treatise, and as being a prime example of a curve that is best defined by a polar equation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Conic sections=== | ||

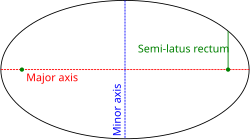

| + | [[Image:Elps-slr.svg|thumb|right|250px|Ellipse, showing semi-latus rectum]] | ||

| + | A conic section with one focus on the pole and the other somewhere on the <math>0^\circ</math> ray (so that the conic's semi-major axis lies along the polar axis) is given by: | ||

| + | :<math>r=\frac{\ell}{1+\epsilon\cos(\theta)}</math> | ||

| + | where <math>\epsilon</math> is the eccentricity and <math>\ell</math> is the semi-latus rectum (the perpendicular distance at a focus from the major axis to the curve). | ||

| + | #If <math>\epsilon>1</math> , this equation defines a hyperbola. | ||

| + | #If <math>\epsilon=1</math> , it defines a parabola. | ||

| + | #If <math>0<\epsilon<1</math> , it defines an ellipse. The special case <math>\epsilon=0</math> of the latter results in a circle of radius <math>\ell</math> . | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Resources== | ||

* [https://mathresearch.utsa.edu/wikiFiles/MAT1093/Polar%20Equations%20and%20Graphs/Esparza%201093%20Notes%205.2.pdf Polar Equations and Graphs]. Written notes created by Professor Esparza, UTSA. | * [https://mathresearch.utsa.edu/wikiFiles/MAT1093/Polar%20Equations%20and%20Graphs/Esparza%201093%20Notes%205.2.pdf Polar Equations and Graphs]. Written notes created by Professor Esparza, UTSA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Licensing == | ||

| + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Polar_Introduction Polar Introduction, Wikibooks] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 17:08, 28 October 2021

The polar coordinate system is a two-dimensional coordinate system in which each point on a plane is determined by an angle and a distance. The polar coordinate system is especially useful in situations where the relationship between two points is most easily expressed in terms of angles and distance; in the more familiar Cartesian coordinate system or rectangular coordinate system, such a relationship can only be found through trigonometric formulae.

As the coordinate system is two-dimensional, each point is determined by two polar coordinates: the radial coordinate and the angular coordinate. The radial coordinate (usually denoted as ) denotes the point's distance from a central point known as the pole (equivalent to the origin in the Cartesian system). The angular coordinate (also known as the polar angle or the azimuth angle, and usually denoted by or ) denotes the positive or anticlockwise (counterclockwise) angle required to reach the point from the 0° ray or polar axis (which is equivalent to the positive -axis in the Cartesian coordinate plane).

Contents

Plotting points with polar coordinates

Each point in the polar coordinate system can be described with the two polar coordinates, which are usually called (the radial coordinate) and θ (the angular coordinate, polar angle, or azimuth angle, sometimes represented as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \phi} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle t} ). The coordinate represents the radial distance from the pole, and the θ coordinate represents the anticlockwise (counterclockwise) angle from the ray (sometimes called the polar axis), known as the positive Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x} -axis on the Cartesian coordinate plane.

For example, the polar coordinates would be plotted as a point 3 units from the pole on the ray. The coordinates would also be plotted at this point because a negative radial distance is measured as a positive distance on the opposite ray (the ray reflected about the origin, which differs from the original ray by ).

One important aspect of the polar coordinate system, not present in the Cartesian coordinate system, is that a single point can be expressed with an infinite number of different coordinates. This is because any number of multiple revolutions can be made around the central pole without affecting the actual location of the point plotted. In general, the point Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (r,\theta)} can be represented as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (r,\theta\pm360^\circ k)} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (-r,\theta\pm(2k+1)180^\circ)} , where Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} is any integer.

The arbitrary coordinates Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (0,\theta)} are conventionally used to represent the pole, as regardless of the θ coordinate, a point with radius 0 will always be on the pole. To get a unique representation of a point, it is usual to limit Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r} to negative and non-negative numbers Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r\ge0} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta} to the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [0,360^\circ)} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (-180^\circ,180^\circ]} (or, in radian measure, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [0,2\pi)} or Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (-\pi,\pi]} ).

Angles in polar notation are generally expressed in either degrees or radians, using the conversion Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 2\pi\ \text{rad}=360^\circ} . The choice depends largely on the context. Navigation applications use degree measure, while some physics applications (specifically rotational mechanics) and almost all mathematical literature on calculus use radian measure.

Converting between polar and Cartesian coordinates

The two polar coordinates Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r,\theta} can be converted to the Cartesian coordinates Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x,y} by using the trigonometric functions sine and cosine:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x=r\cos(\theta)}

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle y=r\sin(\theta)}

while the two Cartesian coordinates Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle x,y} can be converted to polar coordinate Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r} by

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}} (by a simple application of the Pythagorean theorem).

To determine the angular coordinate Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta} , the following two ideas must be considered:

- For Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r=0} , Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta} can be set to any real value.

- For Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r\ne0} , to get a unique representation for Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta} , it must be limited to an interval of size Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 2\pi} . Conventional choices for such an interval are Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [0,2\pi)} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (-\pi,\pi]} .

To obtain Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta} in the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [0,2\pi)} , the following may be used (Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \arctan} denotes the inverse of the tangent function):

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta= \begin{cases} \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)&\text{if }x>0\text{ and }y\ge0\\ \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+2\pi&\text{if }x>0\text{ and }y<0\\ \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+\pi&\text{if }x<0\\ \frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y>0\\ \frac{3\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y<0 \end{cases}}

To obtain in the interval Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (-\pi,\pi]} , the following may be used:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta= \begin{cases} \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)&\text{if }x>0\\ \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)+\pi&\text{if }x<0\text{ and }y\ge0\\ \arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)-\pi&\text{if }x<0\text{ and }y<0\\ \frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y>0\\ -\frac{\pi}{2}&\text{if }x=0\text{ and }y<0 \end{cases}}

One may avoid having to keep track of the numerator and denominator signs by use of the atan2 function, which has separate arguments for the numerator and the denominator.

Polar equations

The equation defining an algebraic curve expressed in polar coordinates is known as a polar equation. In many cases, such an equation can simply be specified by defining Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r} as a function of . The resulting curve then consists of points of the form Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \big(r(\theta),\theta\big)} and can be regarded as the graph of the polar function .

Different forms of symmetry can be deduced from the equation of a polar function . If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(-\theta)=r(\theta)} the curve will be symmetrical about the horizontal Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (0^\circ/180^\circ)} ray, if it will be symmetric about the vertical ray, and if Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(\theta-\alpha^\circ)=r(\theta)} it will be rotationally symmetric Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \alpha^\circ} counterclockwise about the pole.

Because of the circular nature of the polar coordinate system, many curves can be described by a rather simple polar equation, whereas their Cartesian form is much more intricate. Among the best known of these curves are the polar rose, Archimedean spiral, lemniscate, limaçon, and cardioid.

For the circle, line, and polar rose below, it is understood that there are no restrictions on the domain and range of the curve.

Circle

The general equation for a circle with a center at Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (r_0,\phi)} and radius Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} is

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r^2-2rr_0\cos(\theta-\varphi)+r_0^2=a^2}

This can be simplified in various ways, to conform to more specific cases, such as the equation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(\theta)=a}

for a circle with a center at the pole and radius Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} .

Line

Radial lines (those running through the pole) are represented by the equation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta=\varphi}

where Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \phi} is the angle of elevation of the line; that is, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \phi=\arctan(m)} where Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m} is the slope of the line in the Cartesian coordinate system. The non-radial line that crosses the radial line Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta=\phi} perpendicularly at the point Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (r_0,\phi)} has the equation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(\theta)=r_0\sec(\theta-\varphi)}

Polar rose

A polar rose is a famous mathematical curve that looks like a petaled flower, and that can be expressed as a simple polar equation,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(\theta)=a\cos(k\theta+\phi_0)}

for any constant Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \phi_0} (including 0). If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} is an integer, these equations will produce a Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} -petaled rose if Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} is odd, or a Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 2k} -petaled rose if Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} is even. If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} is rational but not an integer, a rose-like shape may form but with overlapping petals. Note that these equations never define a rose with 2, 6, 10, 14, etc. petals. The variable Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} represents the length of the petals of the rose.

Archimedean spiral

The Archimedean spiral is a famous spiral that was discovered by Archimedes, which also can be expressed as a simple polar equation. It is represented by the equation

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r(\theta)=a+b\theta}

Changing the parameter Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} will turn the spiral, while Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle b} controls the distance between the arms, which for a given spiral is always constant. The Archimedean spiral has two arms, one for Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta>0} and one for Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta<0} . The two arms are smoothly connected at the pole. Taking the mirror image of one arm across the Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 90^\circ/270^\circ} line will yield the other arm. This curve is notable as one of the first curves, after the Conic Sections, to be described in a mathematical treatise, and as being a prime example of a curve that is best defined by a polar equation.

Conic sections

A conic section with one focus on the pole and the other somewhere on the Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0^\circ} ray (so that the conic's semi-major axis lies along the polar axis) is given by:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r=\frac{\ell}{1+\epsilon\cos(\theta)}}

where Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \epsilon} is the eccentricity and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \ell} is the semi-latus rectum (the perpendicular distance at a focus from the major axis to the curve).

- If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \epsilon>1} , this equation defines a hyperbola.

- If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \epsilon=1} , it defines a parabola.

- If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0<\epsilon<1} , it defines an ellipse. The special case Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \epsilon=0} of the latter results in a circle of radius Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \ell} .

Resources

- Polar Equations and Graphs. Written notes created by Professor Esparza, UTSA.

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- Polar Introduction, Wikibooks under a CC BY-SA license