Difference between revisions of "The Definite Integral"

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

Suppose <math>f</math> is a continuous function on <math>[a,b]</math> and <math>\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}</math> . Then the ''definite integral'' of <math>f</math> between <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> is | Suppose <math>f</math> is a continuous function on <math>[a,b]</math> and <math>\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}</math> . Then the ''definite integral'' of <math>f</math> between <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> is | ||

:<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\lim_{n\to\infty}A_n=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)\Delta x</math> | :<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\lim_{n\to\infty}A_n=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)\Delta x</math> | ||

| − | where <math>x_i^*</math> are any sample points in the interval <math>[x_{i-1},x_i]</math> and <math>x_k=a+k\cdot\Delta x</math> for <math>k=0,\dots,n</math> . | + | where <math>x_i^*</math> are any sample points in the interval <math>[x_{i-1},x_i]</math> and <math>x_k=a+k\cdot\Delta x</math> for <math>k=0,\dots,n</math> . |

It is a fact that if <math>f</math> is continuous on <math>[a,b]</math> then this limit always exists and does not depend on the choice of the points <math>x_i^*\in[x_{i-1},x_i]</math> . For instance they may be evenly spaced, or distributed ambiguously throughout the interval. The proof of this is technical and is beyond the scope of this section. | It is a fact that if <math>f</math> is continuous on <math>[a,b]</math> then this limit always exists and does not depend on the choice of the points <math>x_i^*\in[x_{i-1},x_i]</math> . For instance they may be evenly spaced, or distributed ambiguously throughout the interval. The proof of this is technical and is beyond the scope of this section. | ||

===Notation=== | ===Notation=== | ||

| − | When considering the expression, <math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx</math> (read "the integral from <math>a</math> to <math>b</math> of the <math>f</math> of <math>x</math> <math>dx</math>"), the function <math>f</math> is called the ''integrand'' and the interval <math>[a,b]</math> is the interval of integration. Also <math>a</math> is called the ''lower limit'' and <math>b</math> the ''upper limit'' of integration. | + | When considering the expression, <math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx</math> (read "the integral from <math>a</math> to <math>b</math> of the <math>f</math> of <math>x</math> <math>dx</math>"), the function <math>f</math> is called the ''integrand'' and the interval <math>[a,b]</math> is the interval of integration. Also <math>a</math> is called the ''lower limit'' and <math>b</math> the ''upper limit'' of integration. |

[[Image:signed-area.png|thumb|right|300px|Figure 4: The integral gives the signed area under the graph.]] | [[Image:signed-area.png|thumb|right|300px|Figure 4: The integral gives the signed area under the graph.]] | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

:<math>\sum_{i=1}^n a^2=a^2\sum_{i=1}^n 1=na^2</math> | :<math>\sum_{i=1}^n a^2=a^2\sum_{i=1}^n 1=na^2</math> | ||

:<math>\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{2a(b-a)i}{n}=\frac{2a(b-a)}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n i=\frac{2a(b-a)}{n}\cdot\frac{n(n+1)}{2}</math> | :<math>\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{2a(b-a)i}{n}=\frac{2a(b-a)}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n i=\frac{2a(b-a)}{n}\cdot\frac{n(n+1)}{2}</math> | ||

| − | For the third sum we have to use a | + | For the third sum we have to use a formula |

:<math>\sum_{i=1}^n i^2=\frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}</math> | :<math>\sum_{i=1}^n i^2=\frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}</math> | ||

to get | to get | ||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

There is a special case of this rule used for integrating constants: | There is a special case of this rule used for integrating constants: | ||

| − | If <math>c</math> is constant then <math>\int\limits_a^b c\ dx=c(b-a)</math> | + | If <math>c</math> is constant then <math>\int\limits_a^b c\ dx=c(b-a)</math> |

When <math>c>0</math> and <math>a<b</math> this integral is the area of a rectangle of height <math>c</math> and width <math>b-a</math> which equals <math>c(b-a)</math> . | When <math>c>0</math> and <math>a<b</math> this integral is the area of a rectangle of height <math>c</math> and width <math>b-a</math> which equals <math>c(b-a)</math> . | ||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

<math>\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)+g(x)\bigr)dx=\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx+\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> | <math>\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)+g(x)\bigr)dx=\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx+\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> | ||

| − | <math>\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx=\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx-\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> | + | <math>\int\limits_a^b \bigl(f(x)-g(x)\bigr)dx=\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx-\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> |

As with the constant rule, the addition rule follows from the addition rule for limits: | As with the constant rule, the addition rule follows from the addition rule for limits: | ||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

:<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx\ge\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> | :<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx\ge\int\limits_a^b g(x)dx</math> | ||

*Suppose <math>M\ge f(x)\ge m</math> for all <math>x\in[a,b]</math> . Then | *Suppose <math>M\ge f(x)\ge m</math> for all <math>x\in[a,b]</math> . Then | ||

| − | :<math>M(b-a)\ge\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx\ge m(b-a)</math> | + | :<math>M(b-a)\ge\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx\ge m(b-a)</math> |

If <math>f(x)\ge 0</math> then each of the rectangles in the Riemann sum to calculate the integral of <math>f</math> will be above the <math>y</math> axis, so the area will be non-negative. If <math>f(x)\ge g(x)</math> then <math>f(x)-g(x)\ge 0</math> and by the first property we get the second property. Finally if <math>M\ge f(x)\ge m</math> then the area under the graph of <math>f</math> will be greater than the area of rectangle with height <math>m</math> and less than the area of the rectangle with height <math>M</math> (see [[:File:Integral_comparison_1.png|Figure 7]]). So | If <math>f(x)\ge 0</math> then each of the rectangles in the Riemann sum to calculate the integral of <math>f</math> will be above the <math>y</math> axis, so the area will be non-negative. If <math>f(x)\ge g(x)</math> then <math>f(x)-g(x)\ge 0</math> and by the first property we get the second property. Finally if <math>M\ge f(x)\ge m</math> then the area under the graph of <math>f</math> will be greater than the area of rectangle with height <math>m</math> and less than the area of the rectangle with height <math>M</math> (see [[:File:Integral_comparison_1.png|Figure 7]]). So | ||

| Line 194: | Line 194: | ||

Suppose <math>a<c<b</math> . Then | Suppose <math>a<c<b</math> . Then | ||

| − | :<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^c f(x)dx+\int\limits_c^b f(x)dx</math> | + | :<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^c f(x)dx+\int\limits_c^b f(x)dx</math> |

Again suppose that <math>f</math> is positive. Then this property should be interpreted as saying that the area under the graph of <math>f</math> between <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> is the area between <math>a</math> and <math>c</math> plus the area between <math>c</math> and <math>b</math> (see [[:File:Integral_linear_endpoints.png|Figure 8]]). | Again suppose that <math>f</math> is positive. Then this property should be interpreted as saying that the area under the graph of <math>f</math> between <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> is the area between <math>a</math> and <math>c</math> plus the area between <math>c</math> and <math>b</math> (see [[:File:Integral_linear_endpoints.png|Figure 8]]). | ||

[[Image:Integral_linear_endpoints.png|thumb|300px|right|Figure 8: Illustration of the property of additivity with respect to endpoints]] | [[Image:Integral_linear_endpoints.png|thumb|300px|right|Figure 8: Illustration of the property of additivity with respect to endpoints]] | ||

| − | Extension of Additivity with respect to limits of integration | + | {{Calculus/Def|text= '''Extension of Additivity with respect to limits of integration'''<br> |

| − | |||

When <math>a=b</math> we have that <math>\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}=0</math> so | When <math>a=b</math> we have that <math>\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}=0</math> so | ||

:<math>\int\limits_a^a f(x)dx=0</math> | :<math>\int\limits_a^a f(x)dx=0</math> | ||

| Line 207: | Line 206: | ||

With these definitions, | With these definitions, | ||

:<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^c f(x)dx+\int\limits_c^b f(x)dx</math> | :<math>\int\limits_a^b f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^c f(x)dx+\int\limits_c^b f(x)dx</math> | ||

| − | whatever the order of <math>a,b,c</math> . | + | whatever the order of <math>a,b,c</math> . |

===Even and odd functions=== | ===Even and odd functions=== | ||

| Line 218: | Line 217: | ||

If <math>f</math> is a continuous even function then for any <math>a</math>, | If <math>f</math> is a continuous even function then for any <math>a</math>, | ||

| − | :<math>\int\limits_{-a}^a f(x)dx=2\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx</math> | + | :<math>\int\limits_{-a}^a f(x)dx=2\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx</math> |

Suppose <math>f</math> is an odd function and consider first just the integral from <math>-a</math> to <math>0</math> . We make the substitution <math>u=-x</math> so <math>du=-dx</math> . Notice that if <math>x=-a</math> then <math>u=a</math> and if <math>x=0</math> then <math>u=0</math> . Hence | Suppose <math>f</math> is an odd function and consider first just the integral from <math>-a</math> to <math>0</math> . We make the substitution <math>u=-x</math> so <math>du=-dx</math> . Notice that if <math>x=-a</math> then <math>u=a</math> and if <math>x=0</math> then <math>u=0</math> . Hence | ||

| Line 240: | Line 239: | ||

:<math>\int\limits_{-a}^0 f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^0 f(-u)(-du)=-\int\limits_a^0 f(-u)du=\int\limits_0^a f(-u)du=\int\limits_0^a f(u)du</math> | :<math>\int\limits_{-a}^0 f(x)dx=\int\limits_a^0 f(-u)(-du)=-\int\limits_a^0 f(-u)du=\int\limits_0^a f(-u)du=\int\limits_0^a f(u)du</math> | ||

where the last step has used the evenness of <math>f</math> . Since <math>u</math> is just a dummy variable, we can replace it with <math>x</math> . Then | where the last step has used the evenness of <math>f</math> . Since <math>u</math> is just a dummy variable, we can replace it with <math>x</math> . Then | ||

| − | :<math>\int\limits_{-a}^a f(x)dx=\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx+\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx=2\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx</math> | + | :<math>\int\limits_{-a}^a f(x)dx=\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx+\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx=2\int\limits_0^a f(x)dx</math> |

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

| Line 249: | Line 248: | ||

* [https://mathresearch.utsa.edu/wikiFiles/MAT1214/The%20Definite%20Integral/MAT1214-5.3TheDefiniteIntegralNotes.pdf The Definite Integral Notes] created by Professor Eduardo Duenez, UTSA. | * [https://mathresearch.utsa.edu/wikiFiles/MAT1214/The%20Definite%20Integral/MAT1214-5.3TheDefiniteIntegralNotes.pdf The Definite Integral Notes] created by Professor Eduardo Duenez, UTSA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Licensing== | ||

| + | Content obtained and/or adapted from: | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Calculus/Definite_integral Definite integral, Wikibooks: Calculus] under a CC BY-SA license | ||

Latest revision as of 10:25, 28 October 2021

Suppose we are given a function and would like to determine the area underneath its graph over an interval. We could guess, but how could we figure out the exact area? Below, using a few clever ideas, we actually define such an area and show that by using what is called the definite integral we can indeed determine the exact area underneath a curve.

Contents

Introduction

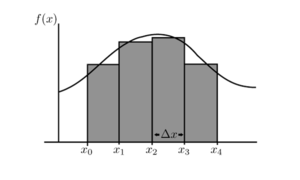

The rough idea of defining the area under the graph of is to approximate this area with a finite number of rectangles. Since we can easily work out the area of the rectangles, we get an estimate of the area under the graph. If we use a larger number of smaller-sized rectangles we expect greater accuracy with respect to the area under the curve and hence a better approximation. Somehow, it seems that we could use our old friend from differentiation, the limit, and "approach" an infinite number of rectangles to get the exact area. Let's look at such an idea more closely.

Suppose we have a function that is positive on the interval and we want to find the area under between and . Let's pick an integer and divide the interval into subintervals of equal width (see Figure 1). As the interval has width , each subinterval has width . We denote the endpoints of the subintervals by . This gives us

Now for each pick a sample point in the interval and consider the rectangle of height and width (see Figure 2). The area of this rectangle is . By adding up the area of all the rectangles for we get that the area is approximated by

A more convenient way to write this is with summation notation.

For each number we get a different approximation. As gets larger the width of the rectangles gets smaller which yields a better approximation (see Figure 3). In the limit of as tends to infinity we get the area .

Definition of the Definite Integral

Suppose is a continuous function on and . Then the definite integral of between and is

where are any sample points in the interval and for .

It is a fact that if is continuous on then this limit always exists and does not depend on the choice of the points . For instance they may be evenly spaced, or distributed ambiguously throughout the interval. The proof of this is technical and is beyond the scope of this section.

Notation

When considering the expression, (read "the integral from to of the of "), the function is called the integrand and the interval is the interval of integration. Also is called the lower limit and the upper limit of integration.

One important feature of this definition is that we also allow functions which take negative values. If for all then so . So the definite integral of will be strictly negative. More generally if takes on both positive and negative values then will be the area under the positive part of the graph of minus the area above the graph of the negative part of the graph (see Figure 4). For this reason we say that is the signed area under the graph.

Independence of Variable

It is important to notice that the variable did not play an important role in the definition of the integral. In fact we can replace it with any other letter, so the following are all equal:

Each of these is the signed area under the graph of between and . Such a variable is often referred to as a dummy variable or a bound variable.

Left and Right Handed Riemann Sums

The following methods are sometimes referred to as L-RAM and R-RAM, RAM standing for "Rectangular Approximation Method."

We could have decided to choose all our sample points to be on the right hand side of the interval (see Figure 5). Then for all and the approximation that we called for the area becomes

This is called the right-handed Riemann sum, and the integral is the limit

Alternatively we could have taken each sample point on the left hand side of the interval. In this case (see Figure 6) and the approximation becomes

Then the integral of is

The key point is that, as long as is continuous, these two definitions give the same answer for the integral.

Examples

Example 1

In this example we will calculate the area under the curve given by the graph of for between 0 and 1. First we fix an integer and divide the interval into subintervals of equal width. So each subinterval has width

To calculate the integral we will use the right-handed Riemann sum. (We could have used the left-handed sum instead, and this would give the same answer in the end). For the right-handed sum the sample points are

Notice that . Putting this into the formula for the approximation,

Now we use the formula

to get

To calculate the integral of between and we take the limit as tends to infinity,

Example 2

Next we show how to find the integral of the function between and . This time the interval has width so

Once again we will use the right-handed Riemann sum. So the sample points we choose are

Thus

We have to calculate each piece on the right hand side of this equation. For the first two,

For the third sum we have to use a formula

to get

Putting this together

Taking the limit as tend to infinity gives

Basic Properties of the Integral

From the definition of the integral we can deduce some basic properties. For all the following rules, suppose that and are continuous on .

The Constant Rule

Constant Rule:

When is positive, the height of the function at a point is times the height of the function . So the area under between and is times the area under . We can also give a proof using the definition of the integral, using the constant rule for limits,

Example

We saw in the previous section that

Using the constant rule we can use this to calculate that

- ,

- .

Example

We saw in the previous section that

We can use this and the constant rule to calculate that

There is a special case of this rule used for integrating constants:

If is constant then

When and this integral is the area of a rectangle of height and width which equals .

Example

The addition and subtraction rule

Addition and Subtraction Rules of Integration:

As with the constant rule, the addition rule follows from the addition rule for limits:

The subtraction rule can be proved in a similar way.

Example

From above and so

Example

The Comparison Rule

Comparison Rule:

- Suppose for all . Then

- Suppose for all . Then

- Suppose for all . Then

If then each of the rectangles in the Riemann sum to calculate the integral of will be above the axis, so the area will be non-negative. If then and by the first property we get the second property. Finally if then the area under the graph of will be greater than the area of rectangle with height and less than the area of the rectangle with height (see Figure 7). So

Linearity with respect to endpoints

Additivity with respect to endpoints:

Suppose . Then

Again suppose that is positive. Then this property should be interpreted as saying that the area under the graph of between and is the area between and plus the area between and (see Figure 8).

{{Calculus/Def|text= Extension of Additivity with respect to limits of integration

When we have that so

Also in defining the integral we assumed that . But the definition makes sense even when , in which case has changed sign. This gives

With these definitions,

whatever the order of .

Even and odd functions

Recall that a function is called odd if it satisfies and is called even if .

Suppose is a continuous odd function. Then for any ,

If is a continuous even function then for any ,

Suppose is an odd function and consider first just the integral from to . We make the substitution so . Notice that if then and if then . Hence

- .

Now as is odd, so the integral becomes

- .

Now we can replace the dummy variable with any other variable. So we can replace it with the letter to give

- .

Now we split the integral into two pieces

- .

The proof of the formula for even functions is similar.

Prove that if is a continuous even function then for any ,

- .

From the property of linearity of the endpoints we have

Make the substitution . when and when . Then

where the last step has used the evenness of . Since is just a dummy variable, we can replace it with . Then

Resources

- Distance Definite Integral (Slides 23-38). PowerPoint file created by Professor Cynthia Roberts, UTSA.

- Definite Integral & Antiderivatives. PowerPoint file created by Professor Cynthia Roberts, UTSA.

- The Definite Integral PowerPoint file created by Dr. Sara Shirinkam, UTSA.

- The Definite Integral Notes created by Professor Eduardo Duenez, UTSA.

Licensing

Content obtained and/or adapted from:

- Definite integral, Wikibooks: Calculus under a CC BY-SA license

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle [x_{i-1},x_{i}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/09cb12a889d47020c8ce7046a2eb60785e00c0b6)

![{\displaystyle x_{i}^{*}\in [x_{i-1},x_{i}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dafeab86f1179399f11208ee27a15c76434aed3d)

![{\displaystyle [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)

![{\displaystyle x\in [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/026357b404ee584c475579fb2302a4e9881b8cce)